Non-reductionism, the idea that mental states are not reducible to physical states, is the new orthodoxy in analytic philosophy of mind. However, in this instalment of our idealism series, in partnership with the Essentia Foundation, Giuseppina D’Oro arques analytic philosophy’s conception of psychology as a natural science of the mind is beholden to a dubious ideology of scientism, therefore not acknowledging the autonomy of the mental.

Reductionism is no longer fashionable in philosophy of mind – the days when the idea that mental states are reducible to physical states was a given are over, and non-reductionism is the new orthodoxy. Yet, while many philosophers of mind would consider themselves card carrying non-reductionists, they also tend to think of psychology as a natural science of the mind. As a result, the defence of the autonomy of the mental one finds in most textbooks operates within a naturalistic framework which fails to acknowledge that humanistic explanations differ in kind from scientific ones.

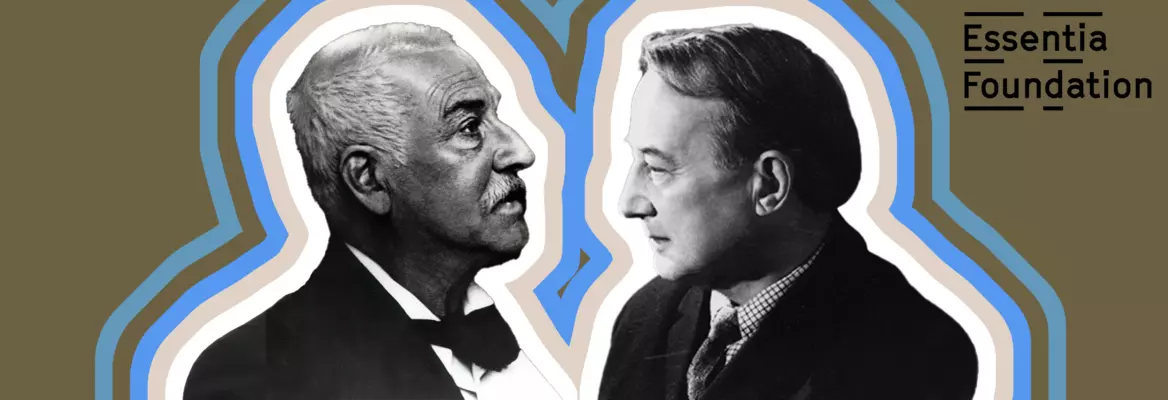

There is however a neglected form of non-reductionism that has its roots in the idealist tradition and is genuinely pluralistic from an explanatory point of view. This form of non-reductionism is motivated by a defence of humanistic understanding and is found in the work of late British idealists, Michael Oakeshott and R.G. Collingwood. They espoused a version of idealism according to which the task of philosophy is not to determine the constitution of reality, whether it is material or immaterial, but to expose the presuppositions on which all knowledge, including scientific knowledge, rests.

SUGGESTED VIEWING Head to Head: Philosophy vs Science With Marika Taylor, Julian Baggini

They argued that the methodological assumptions of scientific inquiry are very different from those of humanistic inquiry and that it is therefore a mistake to think it possible to explain the mind in scientific terms. As a result, unlike most non-reductionists in twentieth century philosophy of mind, they were sceptical of the view that psychology could be legitimately described as the science of the mind and endeavoured to expose the conceptual confusions implicit in the very idea of a natural science of the mind.

In On Human Conduct Oakeshott argued that there are ‘categorially different orders of inquiry’, the humanistic and the scientific, which are concerned with altogether different kinds of goings-on and whose subject matters are sui generis and irreducible. Humanistic inquiries are concerned with ‘”goings-on” the identification of which includes the recognition that they are themselves exhibitions of intelligence.’ Ethics, jurisprudence and aesthetics are distinguishable idioms within the order of inquiry concerned with goings-on identified as expressions of intelligence. Scientific inquiry is concerned with “goings-on” which are not themselves exhibitions of intelligence. Physics, chemistry and psychology are distinguishable idioms within the order of inquiry concerned with processes. Psychology, as one of the idioms of natural science, speaks the language of laws and processes and, as such it is ‘categorially excluded from providing any such understandings.’

___

Oakeshott’s criticism is not directed at psychology as a genuine natural science but at psychology as an ‘all-purpose’ science. The target is not science, which he recognizes as a legitimate cognitive enterprise, but scientism.

___

Join the conversation