‘Westerners’ tend to romanticize traditional African beliefs when they treat them as inherently a-rational; we see ‘African beliefs’ as offering an escape from the constraints of a rationally disenchanted modern world. But anyone who expects to find a refuge from rationality in modern African philosophy should stop reading now: African philosophy is just as critically rational, professional, and institutionalized as its Western relative.

Anyone who is interested in philosophy in general, has at least two reasons to be interested in African philosophy. First, African philosophy queries the habitual universality claims of Western philosophy; second, African philosophy offers insights into dimensions of human experience made uniquely available through African metaphysical beliefs and normative commitments.

Below, I shall briefly speak to both these points in the course of reflecting on the rise of post-independence African philosophy. I shall focus on Anglophone West African philosophical thinking simply because I am most familiar with it.

___

"Hountondji exposed as unwarranted a number of Temples’ assumptions, including the assumption that Africans think collectively rather than individually, and the assumption that all Africans see nature as infused with spiritual forces."

___

Ironically, one of the fathers of modern African philosophy was the Belgian missionary Placide Temples. In 1945, when working in the Congo, Temples published a book called Bantu Philosophy. In it he set out what he claimed to be the philosophical world view (!) of the Bantu, by which he meant sub-Saharan peoples in general. Temples’ position was as radical as it was reactionary: radically, he affirmed that ‘the Bantu’ had a philosophy, so they could think – this was a novel thought in the colonial context. At the same time, Temples contended that the Bantu were not reflectively aware of their philosophical commitments, so they had to have these set out to them by Temples himself – this would have been much more in line with colonial policy.

The subtext to Temples’ endeavour was the need to understand local beliefs in order to more effectively hook Christian doctrine into them. Temples ascribed to the ‘Bantu’ a world-view that was ready-made for completion through Christian doctrine. In the context of growing pressures for independence in the 1950s, Temples’ work came under attack by an emerging generation of Western trained African philosophers.

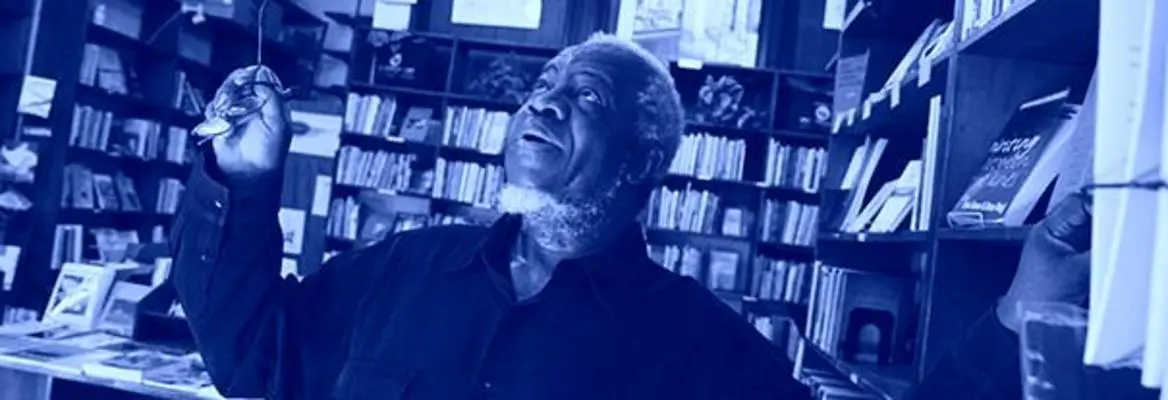

The most devastating critique came from Paulin Hountondji, a French trained philosopher and Husserl scholar from Benin. In a series of articles, later collated into a book, African Philosophy: Myth and Reality, Hountondji exposed as unwarranted a number of Temples’ assumptions, including the assumption that Africans think collectively rather than individually, and the assumption that all Africans see nature as infused with spiritual forces.

Hountondji showed these to be standard Western assumptions about an imaginary ‘African mind’ – they had little to do with actual Bantu thought. Hountondji coined the term ‘ethnophilosophy’ to denote Temples’ pseudo-philosophical approach to his methodologically dubious ethnology. Hountondji’s work advanced a further thesis, namely that there was as yet no such thing as African philosophy. According to Hountondji, while there was no reason why Africans could not engage in philosophical thinking, they had been excluded from doing so by the Western philosophical community, which has historically considered Africans incapable of reasoned argument. Hence, while it was possible for African philosophy to come into being, it did not yet exist.

___

"The Kenyan philosopher Oruka Odera argued that traditional African sages are genuinely philosophical thinkers working within a distinctively oral and practice-focused cultural context."

___

Join the conversation