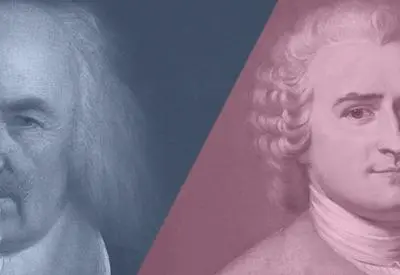

Whether we see humans as essentially good or essentially selfish and violent has been central to our politics, our account of society, and our vision for social progress. Jean-Jacques Rousseau famously defended the former account and Thomas Hobbes the latter. Wojciech Załuski reappraises Hobbes and defends his pessimistic account of human nature.

The question of whether human beings are more prone to do evil or to do good is usually posed in psychological terms: it leads to an inquiry into human predispositions with a view to deciding whether ‘evil’ predispositions prevail over ‘good’ ones, or vice versa. As a result of this way of inquiry, several different views of human nature were distinguished, with the two extreme ones – usually called ‘the Hobbesian view’: human beings are inherently evil, and ‘the Rousseauian view’: human beings are inherently good, and some more nuanced ones located between them (by the way, these standard names of the extreme views are rather misleading, e.g., Rousseau’s complex view of human nature was much more pessimistic that it is usually presented).

SUGGESTED READING

Hobbes vs Rousseau: are we inherently evil?

By Robin Douglass

SUGGESTED READING

Hobbes vs Rousseau: are we inherently evil?

By Robin Douglass

I wish to propose a different way of inquiry, which will consist in looking at this question not from the viewpoint of the ‘subject’ (the predispositions of human beings) but of the ‘object’ (the nature of evil and goodness).

___

The conditions imposed on a truly good act are very restrictive.

___

I shall advance the claim that human beings seem to be more prone to do evil than to do good (as the so called ‘Hobbesian view’ – or some variety of it – implies), and the explanation of this fact can be gainfully sought in the very nature of evil and goodness (in other words, I shall defend the Hobbesian view – or some more nuanced variety of it – but on different grounds than it is usually done). Let me present some arguments for this claim.

The first argument is the commonsensical observation that it is easier to harm than to help someone, to kill that to enliven (the latter obviously being impossible), to destroy than to create, to make unhappy than to make happy. Thus, it seems that, in so far at least as great good and great evil is concerned, it is easier to do evil than to do good.

The second – more sophisticated – argument rests on the Aristotelian account of virtue and vice. This account implies that while it is difficult to be virtuous (in any given circumstances, a virtuous action can be done only in one way, called ‘the mean’), which is why virtuous actions are rare, beautiful, and morally glorious, it is easy to fall into vice: it can be realized in many different ways (e.g., according to Aristotle’s account, in given circumstances, you can manifest fortitude only in one way, but you can be cowardly or reckless – two vices opposed to fortitude – in many different ways).

In fact it is difficult to be virtuous, not only because – to be virtuous – one ought to choose a unique morally good action (‘the mean’), but also because this choice must have some additional features: it must flow from a stable emotional disposition to make such choices, should be made deliberately and disinterestedly – only for the sake of its moral beauty. Thus, the conditions imposed on a truly good act are very restrictive.

Join the conversation