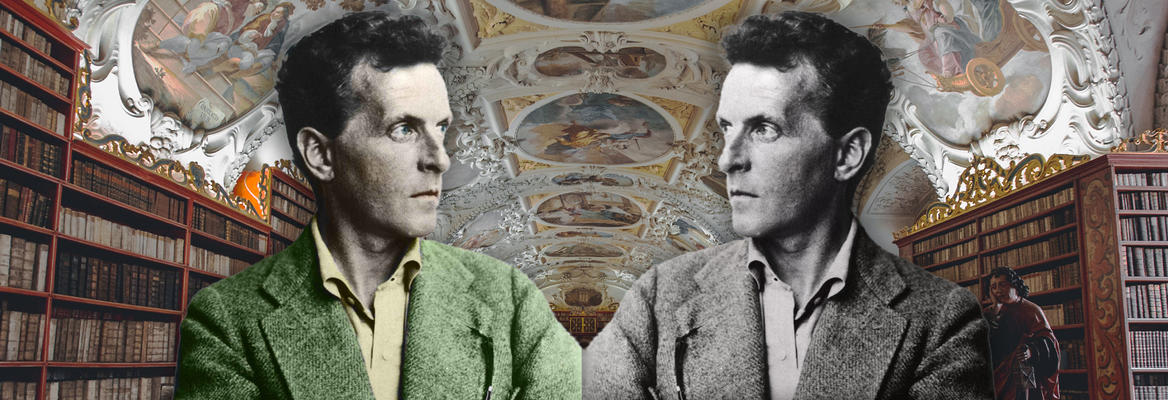

Philosophers seldom change their mind about anything as much as Wittgenstein did about language. The shift from his early masterpiece, the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, to his later work, Philosophical Investigations, is as radical as the move from modern to post-modern philosophy. Wittgenstein leaves behind the view that we can come to know the structure of reality by studying the structure of language, and embraces the idea that language tells us more about ourselves than the world outside us. Lee Braver traces the steps of this incredible transformation.

Few philosophers have given rise to an entire movement, far fewer to two. Along with Heidegger, Wittgenstein counts among this select number in the 20th Century. Wittgenstein capped his early career with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, a dense cryptic book whose truth he found “unassailable and definitive” in finding “on all essential points, the final solution of the problems” (T Preface)--until he came back years later to assail its solutions. He returned to give not just different solutions, but an entirely different take on the nature of knowledge, reality, and what philosophical views about such matters must be like. These two phases of his thought shaped much of roughly the first half of analytic philosophy’s history. The Tractatus brings Frege, Russell, and Moore’s logicism to its culmination and inspired the Vienna Circle. His later work, generally represented by the posthumous Philosophical Investigations, is a foundational work of the ordinary language philosophy practiced by Austin and Ryle and, despite his personal hostility to naturalism, contains elements that pushed analytic thought in that direction where Quine and others then took over. One of the central topics Wittgenstein changed his mind about was on the question of realism - whether we can know the world as it really is and whether our language can map onto reality.

Kant had put this question on a new revolutionary footing by turning the inquiry away from its exclusive focus on the object of inquiry–reality–to the subject of knowledge–the inquirer. His transcendental idealism argues that our mind interacts with what it knows, making it impossible to ever know reality as it is in-itself but only as it is for-us. We can never see the light in the refrigerator turned off because the only way to see it is by opening the door, which turns it on. The standard origin story of analytic philosophy traces it to Russell and Moore use of Fregean logic to overcome Kant’s predicament. “The study of logic becomes the central study in philosophy… [which] in our own day, is becoming scientific through the simultaneous acquisition of new facts and logical methods” (Russell 1929, 259–60).

___

The Tractatus uses logic as a decoder ring of reality: once correlated, we can read the deep structure of reality from the rules of logic.

___

Join the conversation