Where does Russia’s geopolitical future lie? Asia and the Global South offer growing markets, and Putin’s war with Ukraine has seen him embrace China as an ally. But Putin is increasingly reliant on what Mark Galeotti calls the “minigarchs”: ambitious officials in the second echelon of power in Russia, who are the ones who actually execute Putin’s policies. And the minigarchs – the first truly post-Soviet political generation in Russia – haven’t yet bought into Putin’s worldview. They worry that Russia risks becoming China’s vassal, and see an opportunity for Russia to attempt to recover friendly relations with Europe, while the US vacates the continent in its pivot to Asia. In this interview with the IAI, Galeotti suggests that Russia’s future depends on the outcome of this struggle within the minigarchy.

Alasdair Craig: In your book, Downfall, about the rise and fall of Yevgeny Prigozhin, you use the term “minigarch” to describe him. What is a Russian minigarch?

Mark Galeotti: This reflects the odd kind of hybrid state that Russia is. In many ways, Russia is like any other modern, institutionalised, bureaucratic state in which power is exerted through institutions, ministries and the like. However, on top of it, there is this almost medieval personalistic court, and in that context we tend to focus on the people there closest to Putin, who tend to be of the same generation, with the same backgrounds – products of the Soviet era – and the same worldview. These are the oligarchs.

However, we tend not to look at what – if we’re thinking of it in almost tsarist terms – are not the aristocrats at the top (the “Boyars” in the old Russian parlance) but the gentry, the lesser aristocrats, who are vastly more numerous and are actually doing the work of running the country for Putin. In the economy, we could think of them as the “minigarchs” compared with the oligarchs. But this is replicated right across the system, from the government apparatus through to the ministries of the military, the police, and such like. All of these have this second echelon of people who are hungry to get into the top level.

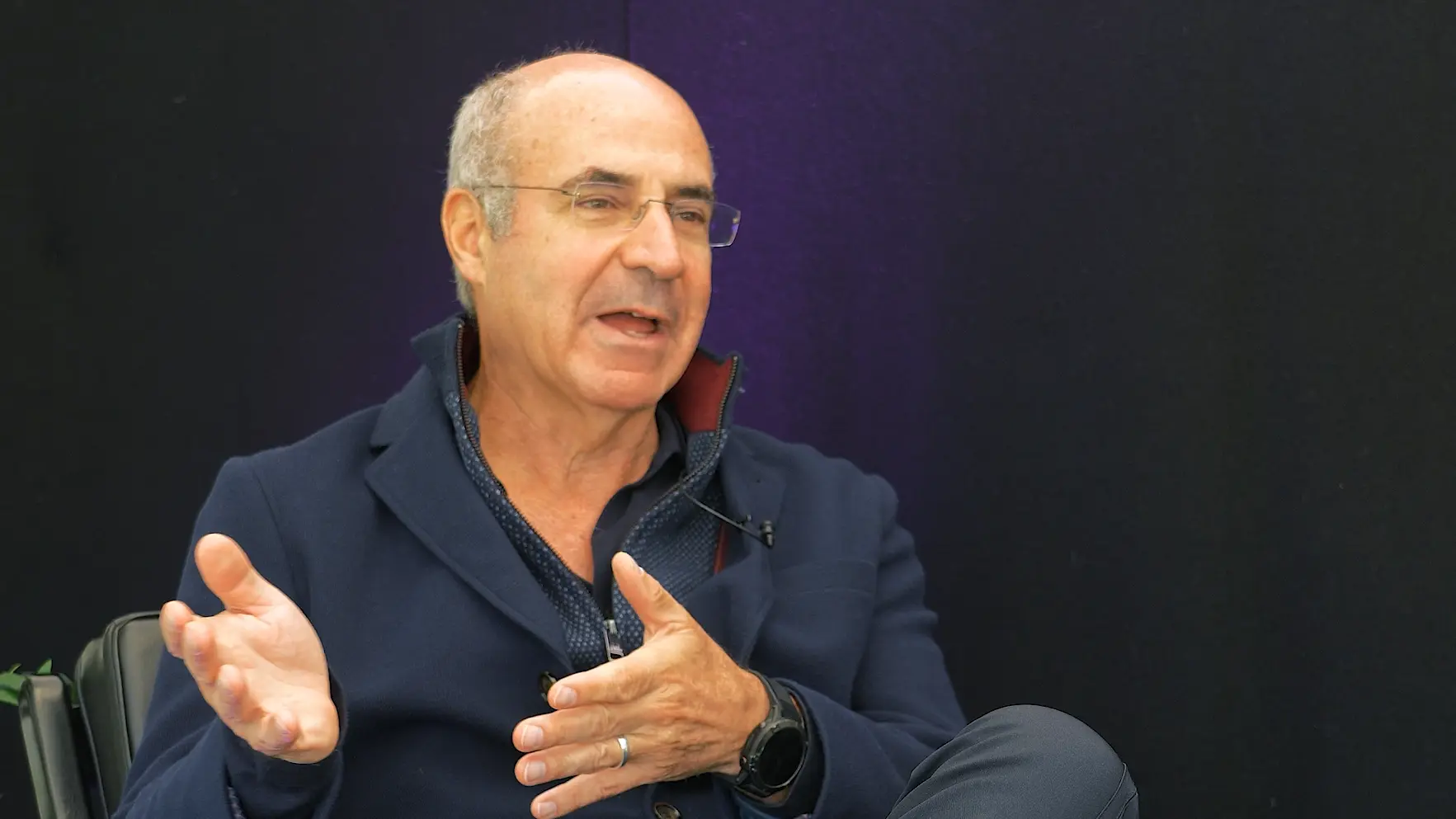

SUGGESTED VIEWING Bill Browder On Surviving Putin With Bill Browder

AC: Is it fair to say that Putin himself was something like a “minigarch” before he became president?

MG: In some ways, yes. Certainly, he hadn’t become vastly wealthy: he’d become deputy mayor of St Petersburg in the 1990s, and in that position we could think of him as an entrepreneur – but a bureaucratic entrepreneur. Instead of buying and selling goods and services, he bought and sold political access. He was everyone’s bagman, he was everyone’s fixer, and so in this respect he became wealthy enough by your and my standards, but never really made it to the top levels of affluence, because that wasn’t what he was after.

AC: This description of Putin as people’s bagman, doing all the work behind the scenes, sounds a bit like Prigozhin himself.

MG: Yeah, exactly, any good bagman needs his own bagman.

AC: What does the power structure in Russia look like at the moment, viz. Putin, the oligarchs and the minigarchs?

MG: Regarding the oligarchs, some of the holdovers from the nineties are often still vastly rich, but they know full well that they are no more than money-managers for the Kremlin, and that if they step out of line they can very quickly lose everything.

Join the conversation