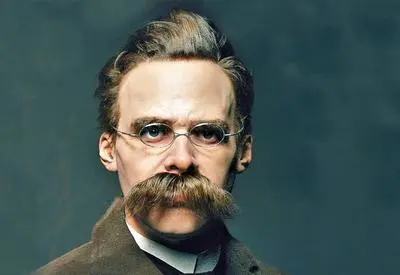

“Who is Andrew Tate?” was one of the most Googled searches in 2022. A kickboxer turned social media personality whose online videos on TikTok alone have amassed 11 billion views, keeps making references to “The Matrix”. The appearance-reality distinction that underlies Tate’s pronouncements has a distinguished pedigree, going all the way back to Plato. But another philosopher, Friedrich Nietzsche, warned of the dangers of believing that reality is only accessible by the few, and lies beyond the ever-changing world of experience, writes Alexis Papazoglou.

“The Matrix has attacked me” were the words of Andrew Tate, an online influencer, supposed multi-millionaire, and former kickboxer, as he was being arrested by police in Romania last December. Tate talks a lot about “The Matrix” in the myriad of videos one can find of him pontificating online. In one such video, when referring again to “The Matrix” he says: “They want to control us. This is what people who are in charge ever wanted from the beginning, control. They want people to comply. And you have to put systems in place to ensure people comply.” So what is Tate really trying to get at when he references the science fiction film franchise? That we are living in a computer simulation? No. What he’s saying is that the world that most of us take as real is a mere appearance, an illusion, and that he has cracked the code and come to see the world as it really is.

SUGGESTED READING

Nietzsche and the perils of denying your self

By Guy Elgat

SUGGESTED READING

Nietzsche and the perils of denying your self

By Guy Elgat

This reference to The Matrix by a certain type of online personality is not new. Conservative YouTube is awash with references to taking “the red pill”, a phrase that became so mainstream that even Ivanka Trump tweeted about it. Being “red-pilled” in conservative online circles became equivalent to, again, waking up from the illusory world curated by the media, the government and other powers to-be, and seeing things as they really are. This idea of there being an illusory world of appearances that most people take to be reality, whereas the real world, Reality, eludes them is, of course, much, much older than this. It goes at least all the way back to Plato. But this distinction between appearance and reality, and the suggestion that only “the chosen ones” can have access to the Real World while the masses are stuck with deceitful appearances, is not only harder to sustain philosophically these days, it is potentially insidious and dangerous.

___

Downgrading people’s everyday lives to mere illusion, and promising them some higher reality, if only they follow your teachings, is a formula used not just by Plato and today’s online hustlers like Andrew Tate but by religions, cults, and conspiracy theorists over the ages.

___

Join the conversation