The topic of colour gives rise to numerous philosophical, aesthetic and psychological questions. In this interview with leading art historian and BAFTA nominated broadcaster, Dr James Fox, we explore the fascinating story of colour, and the profound impact it holds in shaping our thoughts, feelings and actions.

For those able to experience it, colour is inescapable. It surrounds us relentlessly from morning until night, birth until death. It can please us, sadden us, calm us and inspire us. But whilst it continues to be a source of fascination, many mysteries surrounding the nature of colour still remain. Perhaps no man has mined deeper into these varied issues than BAFTA nominated broadcaster, art historian and author of ‘The World According to Colour: A Cultural History’, Dr James Fox. We sat down recently to unpack the multiple meanings of colour.

SUGGESTED READING

Daft Punk and Metaphysics

By James Tartaglia

SUGGESTED READING

Daft Punk and Metaphysics

By James Tartaglia

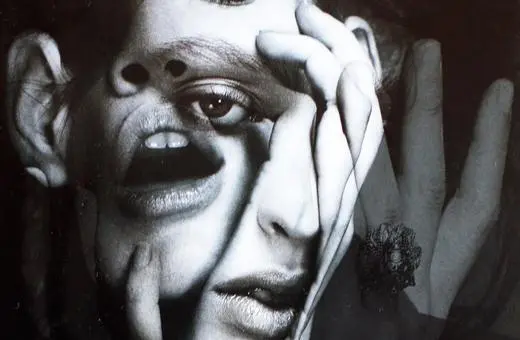

I begin by asking Fox perhaps the most basic, fundamental question; What is colour? He responds by alluding to the curious complexity of this issue. Whilst all around us, it’s very hard to boil it down to a specific definition. He regales the story of Justice Potter Stewart, who in the 1960s was asked to decipher whether a Louis Malle film should be deemed to be pornographic in nature. Stewart famously claimed he could not define pornography but asserted ‘I know when I see it’. For Fox, however, it was Cezanne who had it right: ‘Colour is the place where our brains and the universe meet’. Like Cezanne, Fox places a strong emphasis on this interactive quality between self and world; the process by which our brains interpret the signals our eyes receive.

But beyond this long view on the nature of colour, how should we understand the value of colour to our everyday lives? After all, many of us tend to go about our days without paying particularly close attention to the colours which furnish the world around us.

Colour as a Language

Fox is keen to underscore the importance of colour, arguing that it plays a fundamental part in our human experience and the way we understand reality. He claims that colour has served as an enormously important language and symbol that humans have been using since the beginning. Since the dawn of homo sapiens 300,000 years ago to the present day, colour has remained a constant bearer of symbolic meaning. Red, for instance, has always carried meaning, these days used often to indicate danger, whilst green is a colour which indicates approval. Yet beneath the obvious connotations lie a deeper, subconscious, psychological element. ‘Colour is constantly used to manipulate the way we behave, the way we feel, the way we think’, Fox asserts. ‘It’s a tactic used by governments, brand consultants, fashion designers, advertising agencies and beyond’. He highlights that blue is often supposed to inspire trust, and hence used by numerous financial services companies, whilst red and yellow have been found to stimulate appetite, and as a result end up being used by countless food outlets and manufacturers.

___

Great artists are always using colour in interesting ways- stretching its meaning, stretching its capabilities, changing its symbolic potential and using it in ways that their predecessors could never have imagined

___

Join the conversation