Talk of a new anti-Western alliance changing the balance of world power and finance is everywhere. But BRICS is a long way away from a coherent ideological and geopolitical alliance, let alone a powerful economic block of nations. Russian dissident Sergei Guriev, financier and Putin’s enemy Bill Browder, and Financial Times Europe-China correspondent Yuan Yang debated the future of the global order at HowTheLightGetsIn festival, in London.

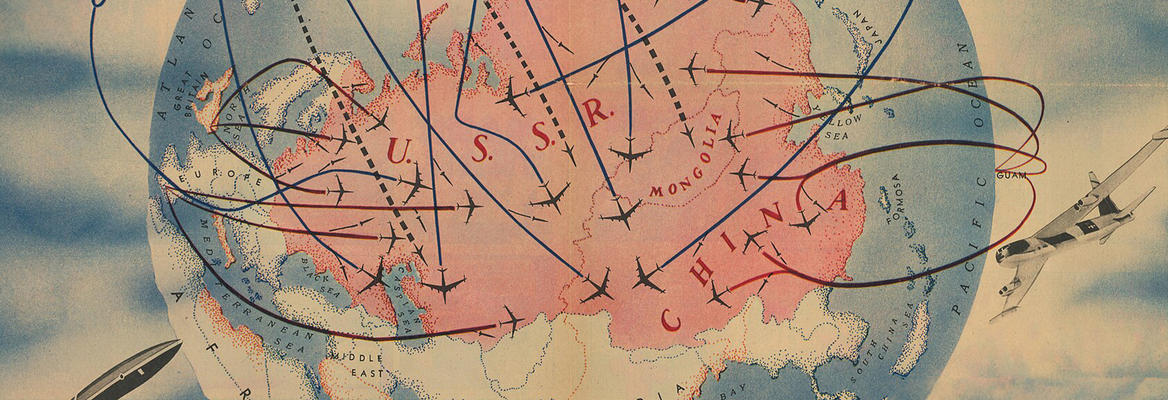

A spectre is haunting the G7, the spectre of BRICS. Or so the recent media storm over the organisation would have you believe. On the surface, this looks like a perfectly reasonable claim. The rise of the East and decline of the West is a narrative that has permeated geopolitics for at least the last 40 years and even further to the decline of Western empire. However, despite the headline figures, the BRICS do not represent that shift. As was argued in the Redrawing the Global Order debate at this year’s HowTheLightGetsIn festival in London, BRICS is a precarious business partnership without the capital, ideology, or trust to challenge the G7.

SUGGESTED READING

BRICS is not a real alliance

By Sergei Guriev

SUGGESTED READING

BRICS is not a real alliance

By Sergei Guriev

Far from the collapse of the Soviet Union marking the permanent ascendance of Western Liberal Democracy, the BRICS nations now command a greater share of global GDP by purchasing power parity (PPP) than the G7. Two members of the BRICS will soon count as both the second and third-largest economies in the world by the end of the decade - China and India. In contrast with the high growth of the BRICS, key members of the G7 appear to be languishing. Italy and Japan’s growth rates have been stagnant for several years, while the BRICS contribution to global growth is 32.1% compared to the G7’s 29.9%. While this may look like a comparatively small difference, never underestimate the power of a compound exponential. They’re also expanding into the development sector. China’s much lauded Belt and Road initiative is now complemented by the New Development Bank, a BRICS backed institution providing targeted financing without the structural adjustment criteria of Western institutions. So after fifteen BRICS summits, with applications to join from Saudi Arabia, Iran and UAE among others, talks of a unified currency and shared geopolitical outlook, will we live in a BRICS dominated future?

___

Much is made of the BRICS having a higher percentage of global GDP than the G7, but importantly this is in purchasing power parity, not absolute terms.

___

Join the conversation