At HowTheLightGetsIn Online 2020 Philip Goff, Bernardo Kastrup and Sophie Grace Chappell debated the fundamental nature of reality. Here, Philip defends panpsychism against the criticisms outlined by Bernardo in that discussion, and presents his own arguments against analytic idealism. Read Bernardo's response here.

For me, the highlight of the recent HLTGI festival was a two-hour discussion I had with Bernardo Kastrup, Sophie-Grace Chappell, and a number of festivalgoers on the Sunday evening. Bernardo defends a form of idealism: roughly the view that the physical world is grounded in a more fundamental, mind-involving reality. I have been meaning for a while to take a deep dive into his papers and really work out what I think of the view, and this event gave me a good excuse.

Although I ultimately don’t quite buy Bernardo’s idealist view, I still think it’s a really important contribution to the science and philosophy of consciousness. It’s early days in the science of consciousness, and the more worked out options we have on the table, the better.

Panpsychists aspire to account for human and animal consciousness in terms of more fundamental forms of consciousness.

Bernardo is an idealist and I’m a panpsychist. Both of us think the fundamental nature of reality is constituted of consciousness. But there are important differences. The main difference is that whilst panpsychists think that the physical world is fundamental, idealists think that there is a more fundamental reality underlying the physical world.

SUGGESTED READING

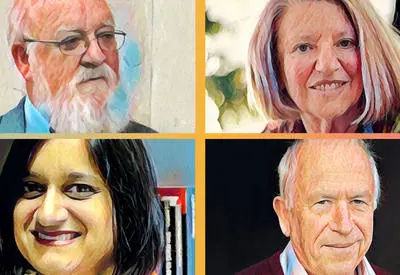

Leading philosophers at HowTheLightGetsIn Global

By

How can a panpsychist think both that the physical world is fundamental and that consciousness is fundamental? The answer is that we believe that fundamental physical properties are forms of consciousness (more on how to make sense of this here). There are two ways of construing this: micropsychism and cosmopsychism. The micropsychist works within a particle-ontology interpretation of physics, and identifies basic forms of consciousness with the physical properties – mass, spin, charge, etc. – of fundamental particles. The cosmopsychist, in contrast, works within a field-ontology interpretation, and identifies fundamental forms of consciousness with universe-wide fields. According to micropsychism, the fundamental conscious subjects are particles, such as electrons and quarks. According to cosmopsychism, there is one fundamental conscious subject: the universe itself.

SUGGESTED READING

Leading philosophers at HowTheLightGetsIn Global

By

How can a panpsychist think both that the physical world is fundamental and that consciousness is fundamental? The answer is that we believe that fundamental physical properties are forms of consciousness (more on how to make sense of this here). There are two ways of construing this: micropsychism and cosmopsychism. The micropsychist works within a particle-ontology interpretation of physics, and identifies basic forms of consciousness with the physical properties – mass, spin, charge, etc. – of fundamental particles. The cosmopsychist, in contrast, works within a field-ontology interpretation, and identifies fundamental forms of consciousness with universe-wide fields. According to micropsychism, the fundamental conscious subjects are particles, such as electrons and quarks. According to cosmopsychism, there is one fundamental conscious subject: the universe itself.

The fact that panpsychism admits of these two interpretations already deflects one of Bernardo’s criticism, namely that it employs a particle ontology, which Bernardo takes to be utterly refuted by contemporary science. Regarding the physics, I think things are not as cut and dried as Bernardo thinks. Whilst many physicists do prefer to think in terms of fields, there are empirically adequate particle-based interpretations of physics. But in any case, the point is moot as a panpsychist need not commit to particles. In fact, in my first book I defended a cosmopsychist form of panpsychism and the view I am currently developing is a form of cosmopsychism.

According to analytic idealism, at the fundamental level there is a single conscious subject: the universal mind.

Join the conversation