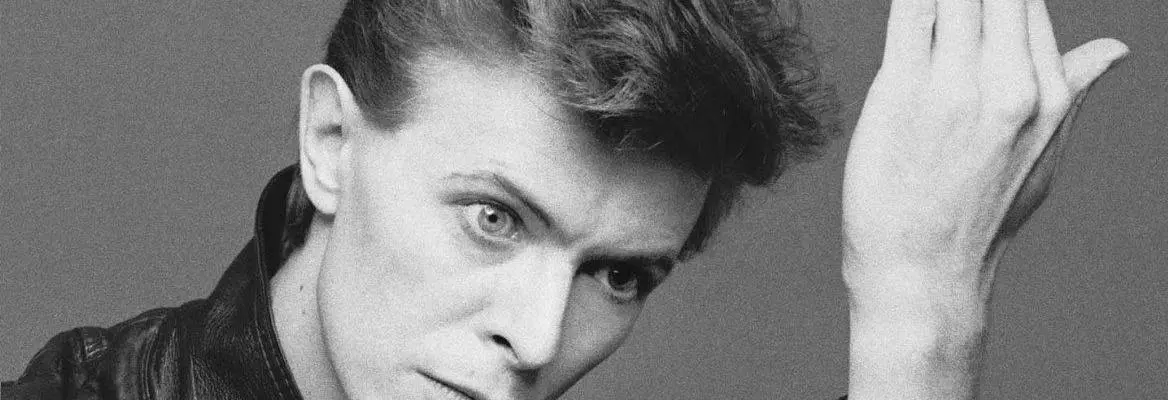

Change, and the apparent necessity and at least the endless capacity for it, subtends the entire process that was David Bowie.

Bowie scoffed in interviews that he was a “chameleon”, involved deeply and publicly in a continual process of “self-reinvention.” In that case, one has to wonder what to make of Bowie’s apparent dismissal of Ziggy Stardust and other personas as merely participants in so many stories about whom there is nothing we need to understand. Bowie confessed that he put on guises, collected voices and then acted them out. And also that he took from Buddhism the transience of it all. So the so-called chameleon of rock, spiritually impressed by the transience of existence, disdains the transience of his own flow of characters and characterizations.

But what is change?—or, what is fundamental change? From the early Greek philosopher Parmenides, we hear that change is movement from where something is to where it is-not. The problem for Parmenides was the status of this “is-not.” How can one change to what one “is-not”? In order to do so, reasoned Parmenides, there must be a preexisting state of “is-not” into which one changes, and the very idea of such a state is contradictory and hence impossible. In short there is no such thing as nothingness, no place where there is not being of some sort, no void, no absolute emptiness, no “is-not”. Hence, no such process as change, much less fundamental change beyond the immediacy of how the world appears to us.

A problem with Parmenides’s view is that it belies ordinary sense experience. A modern version of the Parmenides-static-self can be found in the Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes, whose “I am, I exist” as a thinking thing dissociates the body from the mind/soul/self. In truth Descartes is little concerned with the personal self but is rather motivated to delineate God, mind and material substance. Where exactly the self is located for Descartes is unclear. If it’s in the mind, then the self is a more-or-less permanent object fed by the senses of the body. If it’s in the brain, then the self is a constant conflagration of sensations. But the latter view is hardly Cartesian in spirit. Early in the Meditations Descartes attributes the function of imagination to the “thinking thing” as a form of thought, but later he reneges and thus attributes imagination to the brain. It is difficult to imagine the self independently of imagination. The Cartesian problem is that the self can be either constant or inconstant, depending on where it is located. Which “location” best suits the Meditations? If imagination is a mode of thought, then the self is located in the mind; if not, then it’s in the body. Descartes, in short, leaves us a more sophisticated version of Parmenides regarding the self, and a more confusing one. But at least Descartes rescues sense experience from the scrapheap of the perennially confusing. God doesn’t systematically deceive us.

___

"Bowie is marked by the constancy of his changes, and remained to the end the river into which one couldn’t step twice."

___

Join the conversation