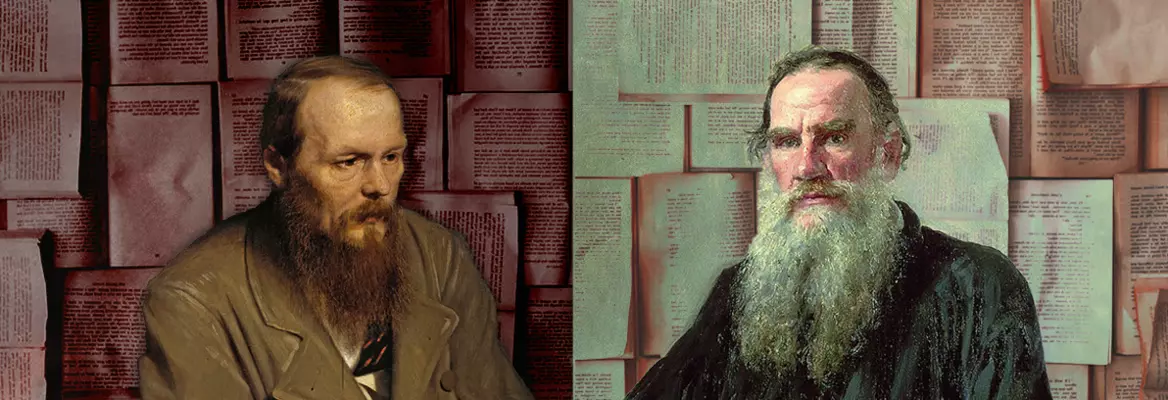

Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky had radically different accounts of religion and its relation to language. In this piece, Professor of Russian John Givens argues that while Tolstoy attempted to create a practical version of Christianity by using readily comprehensible language purged of mysticism to describe the world, it is ultimately Dostoevsky and his language-transcending mysticism which provide readers with a more meaningful account of what it means to embody religion and act in the world accordingly.

Leo Tolstoy and Fyodor Dostoevsky spent the last decades of their lives convinced that the atheism of the nascent revolutionary movement in nineteenth-century Russia and across Europe was both wrong and harmful. However, each struggled with how to articulate their belief in God to a public which increasingly either rejected the idea of faith or viewed religion as a cultural rather than a spiritual force: a set of rituals and practices rather than deeply held beliefs. The problem was one of language. In an age of scepticism and rising secularism, how can one affirm belief without engaging in naïve apologetics? And how does one separate belief from religion? Having rejected the Church as one of the chief obstacles to understanding Jesus’ teachings, Tolstoy certainly had no interest in defending Russian Orthodoxy, though he was passionately committed to the Gospels. Dostoevsky, too, was much more fervently interested in Jesus than the Church that had been founded in his name. Explaining their ardent beliefs in God and Jesus, however, was not easy. Language got in the way.

___

The difficulty is that faith, like God, is largely ineffable.

___

In a letter at age 33, having just finished serving four years of hard labour, Dostoevsky admitted that he was “a child of this century, a child of doubt and disbelief,” but he also described a “symbol of faith” he had formed in which all was “clear and sacred.” He writes: “This symbol is very simple and here is what it is: to believe that there is nothing more beautiful, more profound, more sympathetic, more reasonable, more courageous, and more perfect than Christ; and there not only isn’t, but I tell myself with a jealous love, there cannot be. More than that – if someone succeeded in proving to me that Christ was outside the truth, and if, indeed, the truth was outside Christ, I would sooner remain with Christ than with the truth.” Here, the problem with language is on full display. Carried away by the ardour of his conviction, Dostoevsky strays into problematic theological territory, for a Christ “outside the truth” is, presumably, a non-divine Christ. It seems that Dostoevsky has inadvertently undermined his “symbol of faith” at its inception.

Join the conversation