Science will usher in a utopia and should be worshipped, so believed the 19th-century Russian nihilists. Their ideas would later inspire the Bolsheviks—Lenin even used the title of Chernyshevsky's What Is to Be Done? for his own revolutionary pamphlet. But in seeking to explain away human complexity with scientific certainty, did the Russian nihilists radically misunderstand human nature? And are we repeating their mistakes today? In this article, Slavist and literary critic Gary Saul Morson contrasts the science-worshipping Russian nihilists with Tolstoy, Turgenev, and Dostoevsky, who, he argues, revealed a world too intricate and mysterious to ever be fully understood.

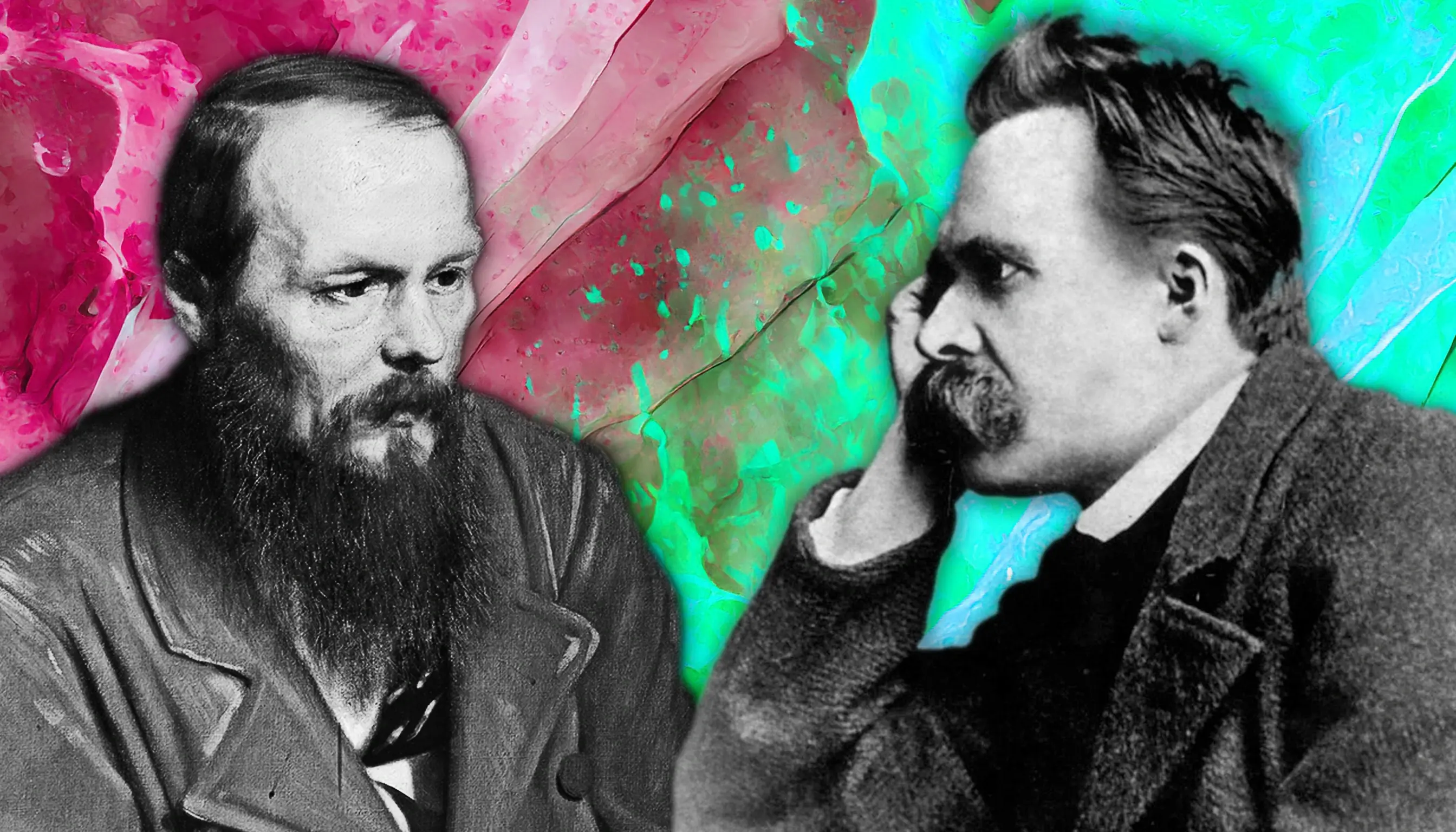

“Nihilist” and “nihilism”—terms typically attributed to novelist Ivan Turgenev—originally referred to a group that arose in Russia around 1860. Today we often call people nihilistic if they extend no hope that conditions can improve. Unqualified pessimists, they regard all grounds for optimism as illusory. We also use the term “nihilism” to describe extreme relativism about the bases of human knowledge. Science, in this view, is just another ideology, based, like all ideologies, on the interests of a ruling class. Accepted knowledge is nothing more than power made into a philosophy justifying it. This kind of nihilism often interprets various philosophers—Hume, Nietzsche, Marx, Freud, Feyerabend, and others—as justifying the claim that one can build on no certain “foundations.”

Neither understanding of nihilism applies to the original Russian nihilists. Far from despairing, they believed that they knew just how to build the perfect society, which, they also held, could be realized in a few years. Regarding “science” as a set of infallible (and mostly metaphysical) dogmas, they deemed their favored social theories scientific and therefore utterly beyond doubt. As their critics observed, these science worshippers missed the whole point of science, openness to contrary evidence.

The group’s leader, Nikolai Chernyshevsky (1828-1889), exercised immense influence. His utopian fiction, What Is to Be Done? (1863)—the question was anything but rhetorical—became the most widely read book among the intelligentsia before the Revolution. Lenin credited it with making him a revolutionary, and the Soviets hailed Chernyshevsky as a thinker in the same league as Marx and Engels. Tolstoy, on the other hand, referred to him as “that gentleman who stinks of bedbugs,” a loathsome figure who has persuaded his followers that “to be outraged, bilious, and spiteful is a commendable thing.”

A conversation among Chernyshevsky, Turgenev, and Dostoevsky illuminates nihilist theses and their critics’ objections. In response to Chernyshevsky’s article “The Russian at the Rendez-vous” (1858), a critique of Turgenev’s novella “Asya,” Turgenev published Fathers and Children (1862), which was in turn answered by What Is to Be Done?. Dostoevsky’s Notes from Underground (1864) then mercilessly parodied What Is to Be Done?.

Chernyshevsky’s article develops a comprehensive, putatively scientific, theory of the human condition, a theory opposed not only to Turgenev’s views but also to the presuppositions of the realist novel as a genre. Such novels, according to Chernyshevsky, reflected ideas from the pre-scientific past.

___

“You have practically reached the limits of human wisdom,” Chernyshevsky concluded, “when you become convinced of the simple truth that every person is exactly like every other one.”

___

Join the conversation