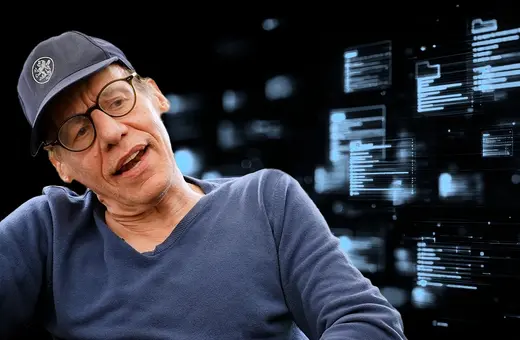

Mathematical models wield miraculous power, but mistaking them for reality has trapped science in a destructive quest for a “Theory of Everything.” Physicist and philosopher Ragner Fjelland argues that this leads to bloated, Frankenstein theories kept alive by clumsy, ad-hoc amendments, which reduce rather than boost science’s power. Fjelland calls for a radical shift in our attitude: we must reorientate towards creating entirely new theories, celebrating rather than lamenting disunity and diversity in science.

Science, from the scientific revolution in the seventeenth century to the present day, has more or less developed in a “reductionist” way. The fundamental assumption is that all sciences may be ordered in a hierarchy that can be represented as an upside-down pyramid. At the top we find the human sciences, and at the bottom physics. Strong (or “ontological”) reductionism maintains that all theories at one level can be completely reduced to the lower level, all the way down to theories of atoms and elementary particles, or whatever is “at the bottom.” In the end, all diversity in the world can be unified in one fundamental theory. Hence it is called a final theory, or a Theory of Everything.

One of the central figures in developing the idea of a Theory of Everything is the Dutch theoretical physicist Gerard 't Hooft, who received a Nobel Prize in physics in 1999 for his work. He emphasizes the non-empirical status of the theory:

There exists no closely resembling alternative theory. This means that any slight change brought about in the rules would make the theory unlikely or inelegant. The theory will be a "package deal": take it, or leave it. This should hold both for the local laws and for the boundary conditions.

This endeavor is not new. On the contrary, it goes all the way back to the birth of Western philosophy 2,500 years ago. The Babylonians made regular astronomical observations during a period of 600 years, from 747 BCE until 150 ACE. They developed mathematical techniques to predict astronomical phenomena, but they made no attempts at explaining them. However, the Greeks developed models, both material and theoretical, to explain the observed phenomena.

The best example is Plato’s late dialogue Timaeus. Here he introduces a divine craftsman, the Demiurge, who has constructed the universe according to an original plan. Plato seems to have thought that the original plan is what is actually real, while the material world is merely an imperfect realization of it. He therefore does not, in the Timaeus, reconstruct the material universe, but the original plan, which can then be used to explain the material universe.

Plato’s aim in producing a theoretical model is to reconstruct the original plan. That is what he carries out in Timaeus—and some modern physicists have embarked on the same project. For example, Einstein’s basic attitude is reflected in the title of Abraham Pais’ biography: “Subtle is the Lord...,” echoing Einstein’s comment, “Subtle is the Lord, but malicious He is not.” In an interview Einstein compared our situation to a child who enters a huge library. The child knows that someone has written the books, but he does not know the languages in which they are written. He suspects that there is a mysterious order, but he does not know what it is.

___

“We have all been working in what Husserl called the Galilean style; that is, we have all been making abstract mathematical models of the universe to which at least the physicists give a higher degree of reality than they accord the ordinary world of sensation.”

Steven Weinberg, Nobel Prize in Physics (1979)

___

Join the conversation