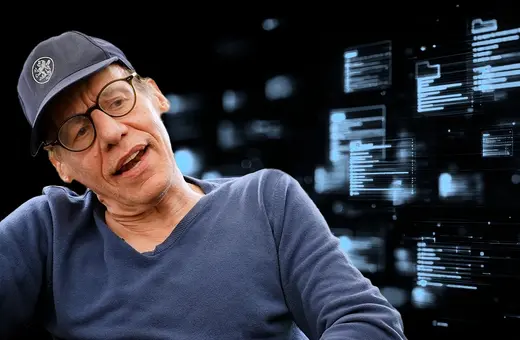

Thomas Kuhn taught us that scientific revolutions arrive only in moments of a crisis of the paradigm. Now, as philosopher Steve Fuller argues, we may be able to intervene without having to wait for a Kuhnian paradigm shift. In a scientific world dominated by computer simulations and unread research, generative AI offers a radical solution. By mining the entirety of scientific knowledge and placing it in the hands of non-experts, AI could trigger a metascientific revolution—one that finally delivers on science’s promise of collective empowerment.

The most influential work on the nature of science for at least the past fifty years has been The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, first published in 1962 by a young physicist-turned-historian, Thomas Kuhn. Although influential, the book has also been widely misunderstood. It is quite common to think—certainly based on the title—that Kuhn was providing a formula for producing scientific revolutions. On the contrary, he was arguing that revolutions only happen once scientists confront insurmountable obstacles in attempting to solve their own research problems. In the Kuhnian jargon, the “paradigm” is then in “crisis.”

Such crises typically involve the presence of phenomena that cannot be explained within the terms set by the paradigm, even after much research has been devoted for many decades—if not centuries—to the matter. Kuhn’s own case in point was the persistent difficulties that physicists working in the Newtonian paradigm faced with accounting for the nature of light, which eventuated in the relativity and quantum revolutions in the early twentieth century. The paradigm that was formed after those revolutions continues to dominate physics research today.

Nowadays, many authors—including accredited scientists—believe that physics is once again in crisis and that a revolution is required to establish a new paradigm. Interestingly, the first call came in 1996 from an editor at Scientific American magazine, John Horgan, whose book The End of Science predicted—accurately, I believe—that the increasing use of computer simulations in cutting edge research across the sciences would shift the site of validation from hard empirical fact to more aesthetic criteria, such as beauty and elegance, which are normally associated with pure mathematics.

___

We can regard what began four hundred years ago as a kind of technical solution to the profoundly fallen nature of humanity.

___

Horgan had interviewed Kuhn himself but went beyond him to suggest that scientific research was becoming the collective realization of an artistic vision that might then be imposed as the lens through which everyone sees the world. This reading of Kuhn makes sense if you think about “paradigm” as meaning “worldview” or “world-picture.” Imagine Newton as being like Rembrandt, both master artists who first sketch a vision and fill in much of the detail but then leave it to others to follow their example and complete the final work.

Horgan was vehemently opposed by the scientific establishment. Nevertheless, he had history on his side. What we now regard as the first ‘scientific revolution’ in seventeenth century Europe started a shift in the source of privileged evidence from the field to the lab. It was ultimately about not trusting your senses until they were systematically mediated, starting with telescopic observation but quickly incorporating all the other instruments that are commonly found in scientific laboratories today – not least computers. In this respect, physics was the vanguard science, followed by chemistry and then biology and the social sciences.

Join the conversation