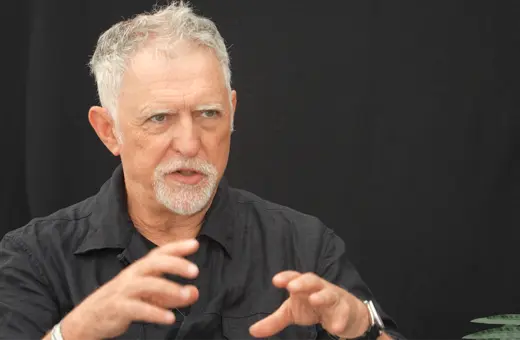

The scientific image of the world seems to suggest free will is impossible for humans. Despite the central role it plays in giving meaning to our lives, it’s all too tempting to dismiss free will as an illusion. But that would be a mistake. Instead of thinking of ourselves as part of a causally determined nature, we need to start with acknowledging that ‘causality’, ‘laws of nature’, and even ‘nature’, are in fact constructs of human consciousness. The causal necessity we seem to detect in nature is nothing more than our own, human projection. What is more, human actions properly understood are distinctly different from natural events – embedded with meaning and possibility. Free will can seem impossible in theory, but it’s fully real, argues Raymond Tallis.

Free will seems impossible in theory. Actions are material events originating from a material body interacting with a material world. All such interactions are governed by the laws of nature. What’s more, they seem to have a causal ancestry that extends beyond anything over which agents can have control – perhaps all the way back to the Big Bang. Worse still, agents rely on a law-governed universe for their actions to be possible and to have predictable, and hence their intended, consequences.

This traditional case for determinism has recently been supplemented by ‘neurodeterminism’ which rests on the assumption that persons are their brains, which are material objects subject to the laws of nature. Neuroscientific studies of voluntary actions have seemed to some thinkers to demonstrate that our brains have decided what we are going to do before we are aware of having made a decision.

Nevertheless, free will appears real in practice: we feel that there is an undeniable, fundamental difference between things we do and things that merely happen to or around us. What’s more, if there were no such difference, our lives would lose much of their meaning. Defending our practical belief in freedom against theoretical objections is perhaps the most important, as well as the most intriguing, challenge of philosophy. Given the stalemate between those who defend and those who deny free will a new approach is needed.

The human construction of nature

My defence of free will rests on the ‘aboutness’ or intentionality of human consciousness. This is the key to the unique nature of human beings as embodied subjects. Intentionality cannot be reduced to the law-governed effects of the material world interacting with the human body or, more specifically, the brain. Seeing an object ‘out there’, for example, is not identical with neural activity triggered by light energy, though the latter is its necessary condition. If there is such a thing as law-governed causality in the case of vision, it applies only to the light getting into the brain but not to the gaze looking out. The same distinction applies to the aboutness of other mental contents – other forms of perception, beliefs, knowledge, thoughts, hopes, and plans.

Intentionality cannot be reduced to the law-governed effects of the material world interacting with the human body or, more specifically, the brain.

Join the conversation