Earlier this year we put the question "How can philosophy help us understand transgender experiences?" to a range of thinkers. You can find some of the answers we have received below. We will be seeking to add to this collection of initial responses in the near future and hope that it will provide a thought provoking set of answers to the complex [and important] question we posed. When theorising about transgender experiences, questions of subjectivity and objectivity, of power, ideology, and authority, frequently get raised. Perhaps the greatest disputes have surrounded the relation between transgender identity and the legal consequences of feeling like one belongs to a different gender than assigned at birth. Just how much the tools of philosophy and theory can help express diverse experiences of being alive is what we've asked a range of thinkers who have written on the subject.

A previous version of this article included a different introductory paragraph, as well as answers from Robin Dembroff, Rebecca Kukla and Susan Stryker. They have since retracted their contributions. You can find a public statement explaining the reasons for their retraction here. A response to this retraction from Holly Lawford-Smith can be found here. We are in the process of seeking out contributions from a broad range of perspectives.

___

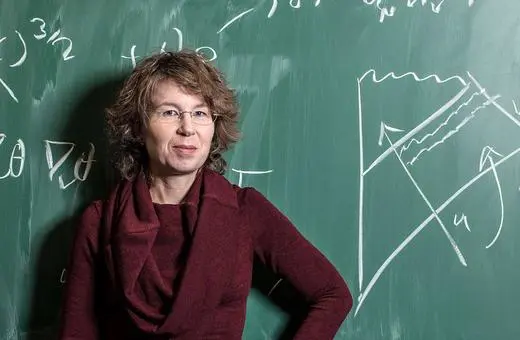

Kathleen Stock

___

Kathleen Stock, Professor of Philosophy, University of Sussex. She has published on aesthetics, fiction, imagination, and sexual objectification.

Philosophy can ask: what is a transgender identity? More generally, it can ask what “identity” is, and interrogate the central role that the notion now plays in contemporary politics. On one interpretation, one’s identity is wholly subjective: it’s whatever you believe you are, right now, where your beliefs guarantee success – if you now believe that you are such-and-such, then being such-and-such is your identity, and there’s no way you can be wrong about that. Sometimes we hear that identities include, not just being trans or not, but also having a sexual orientation: being gay, or heterosexual, or bisexual. But if, for instance, “subjectively believing you are heterosexual” is equivalent to “actually being heterosexual”, then this presumably means you are automatically heterosexual as long as you feel that term applies to you. And this looks wrong. Aren’t there independent, non-subjective conditions to be fulfilled, to count as being a heterosexual? You have to be genuinely attracted to the opposite sex, for one. Lots of people believe they’re straight but aren’t. Self-deception is possible. So possession of a heterosexual identity, in an interesting sense, seems to require more than just subjective belief. If that’s right, then we should think harder about making a transgender identity only a matter of what one subjectively feels is true about oneself right now.

___

Julie Bindel

___

Julie Bindel is a British writer, radical feminist, and co-founder of the law-reform group Justice for Women, which since 1991 has helped women who have been prosecuted for killing violent male partners.

Philosophy can change the way we understand both the social imposition of gender identity, because gender is nothing more and nothing less than a social construction based on sex stereotypes. By thinking philosophically about what it means to be a woman, or a man, we can differentiate between biological sex, and the rules imposed upon women and girls, in order to render us socially, sexually, socially and politically insubordinate to men.

Join the conversation