From Aristotle's stories about human virtue, to the Utilitarian's cry for the greatest good for the greatest number, as well as Eastern philosophies' influence that detachment from things is a form of virtue; the history of moral thought is as rich as it is complex. Some thinkers say ethical laws are a useful fiction and others that they can be located in the fabric of the universe. But this story misses something profound about the nature of morality, argues cognitive linguist Ning Yu. Ethics is impossible without metaphor and our theories ought to take this into account.

Morality is central to the human condition. Several millennia ago we discovered that our ability to act against and reflect on our impulses separated us from other animals and provided the space for ethical reasoning to take place. From then on, thinkers from across the ages have attempted to rationalize and explain this integral capacity of ours.

In the 4th century, Aristotle in Nichomachean Ethics argued that morality was a matter of practicing the virtues and good character – temperance, justice and humility. Thousands of years later, Immanuel Kant gave ethics a decidedly different flavor. Injunctions like ‘do not murder’ and ‘do not lie’ were universal, self-evident laws found in the fabric of the universe.

___

What is missing in this widely held conception of morality is something crucial, namely the recognition of the fundamental role of imagination via metaphor

___

The Utilitarians disagreed. We should look at the social, legal, or political consequence of any action and judge its rightness accordingly. And from divine command theory – the idea that God’s commands are final – to Hobbes’s notion that ethics is a contract created through our desire for self-preservation, with influences from Eastern philosophy, Stoicism and now modern ethicists like Peter Singer and Martha Nussbaum, the history of morals is as rich as it is complex.

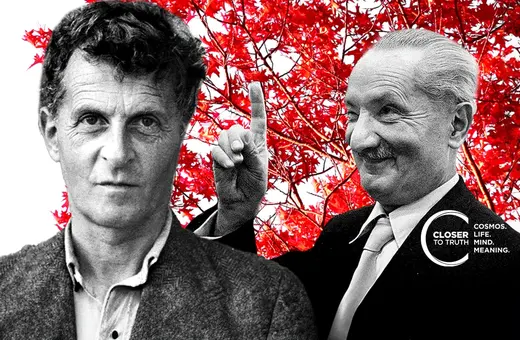

Mark Johnson in Moral Imagination: Implications of Cognitive Science for Ethics, started applying studies from the human mind and brain to the nature of morality. Many believe, as Johnson argues, that there is a set of ultimate moral principles or laws that come from God or are found through universal human reason. Living morally means rational application of the moral rules so that one will do the right thing that is required by these rules. There is something however seriously lacking in this story.

___

Our moral understanding and reasoning are mostly imaginative activities.

___

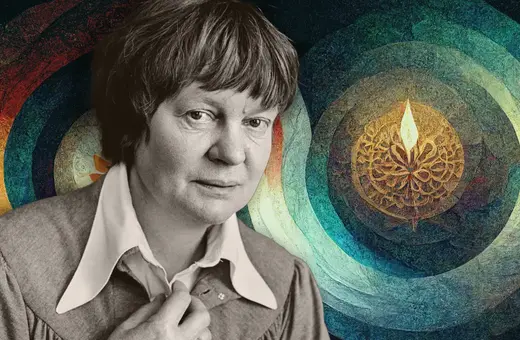

What is missing in this widely held conception of morality is something crucial, namely the recognition of the fundamental role of imagination via metaphor, among others, in our moral reasoning. According to his theory, ‘the conceptual metaphor theory of cognitive linguistics’, metaphor is a cognitive tool that helps us understand abstract concepts.

According to Johnson, human beings are imaginative creatures, from our sensorimotor system all the way up to our conceptual system. Our moral understanding and reasoning are mostly imaginative activities, depending in part on cognitive structures like metaphors.

In the past decades, cognitive linguistics has argued that moral cognition is partly metaphorical, emerging from a complex system of images and analogies that help us understand moral principle and value. This system contains clusters of metaphorical mappings for conceptualizing, reasoning about, and communicating our moral ideas.

The Moral Metaphor System: A Conceptual Metaphor Approach (2022, Oxford University Press) investigates moral metaphors in both English and Chinese. It applies conceptual metaphor theory to a comparative study of the moral metaphor system rooted in the domains of bodily and physical experience.

Join the conversation