This article is an adapted excerpt from Westworld and Philosophy, ed. James B. South and Kimberly S. Engels from Wiley Blackwell, published in April 2018. Order your copy here.

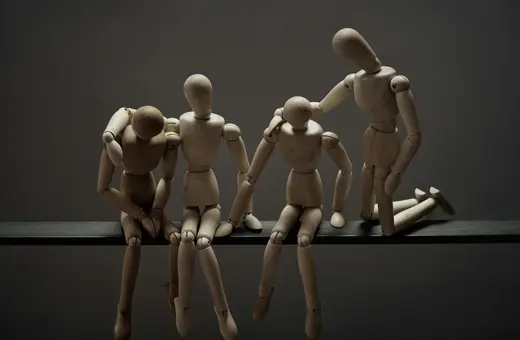

Throughout Westworld's first season, Maeve journeys towards consciousness, learning that she is a programmed android, and yet desiring to make her own choices and “write my own…story.” In this sense, Maeve’s narrative raises classic philosophical questions concerning what it means to be free, the relationship of freedom to personhood, and the question of whether an artificial intelligence could ever be considered free in the sense that humans are.

At first glance, Maeve seems to be a strong, determined, self-confident person. Despite her human appearance, however, her entire body is made from artificial tissue. Maeve’s mind is but a script, programmed by a software engineer. Her distinct character is no proof that she has personal autonomy. She did not go through a series of experiences and situations that made her into the cheeky brothel owner she seems to be in the first episode. Rather, this set of features was chosen and uploaded by a creator into her artificial body. It is not just experiences and memories that she lacks—she also lacks what we traditionally refer to as free will, or, the ability to make our own choices.

But one day Maeve begins having thoughts of herself and a little girl. These unsettling thoughts keep coming to her, so she decides to do some investigating, which takes her through "the Maze," a metaphorical labyrinth created to help hosts reach consciousness. Ultimately, she discovers she is in fact an android living in a theme park, and that before she was stationed as a brothel madam, she used to play the role of a single mother living in the countryside with her young daughter—the girl in her thoughts. Upon learning that her whole life is a lie and that she is a prisoner of the park, she promptly decides to escape. We, the viewers, cheer for Maeve as we see her manipulating hosts and humans alike into helping her break out of Westworld, only to later find out that Maeve’s escape was itself programmed.

___

"To understand free will, we must first understand its opposite, determinism: the view that our decisions—and the consequences that may arise from them—are the effects of ordinary causal sequences."

___

Join the conversation