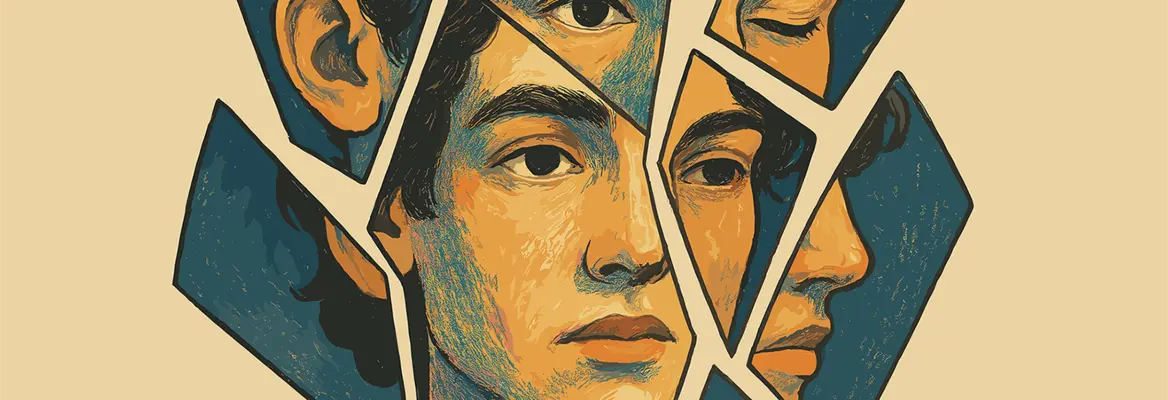

The self is always alienated from itself. Even Descartes' “I think, therefore I am” suggests a form of alienation because it is unclear who or what the “I” is that is thinking. For this reason, we are always, in a sense, inauthentic and performing as a kind of character. University of Wuppertal philosopher, Gigla Gonashvili, argues that even though our thoughts are not our own, we should allow them to play spontaneously, and through writing, attempt to carve out a more authentic self by attempting to find a language that is authentically our own.

Alienation is not merely a psychological or social phenomenon, but rather something that emerges within thinking itself, inasmuch as it expresses a truth about the thinking subject. In fact, the Cartesian “I think, therefore I am,” despite being ultimately put forward as an absolute certainty, contains within it the possibility of spontaneous alienation – precisely because it is not clear who this “I” is that thinks and, moreover, experiments with the givenness of their self. As we know, for Descartes, the solitary meditator is no longer a body or a rational animal (as first formulated by Aristotle and passed down through the scholastic tradition), but a thinker who, through the spontaneous creation of expressions, resists the dissolution of sense or rational certainties. Curiously, the same aspiration can be found in the thought of the 20th-century French artist Antonin Artaud, who, through his efforts to express the disappearance of the thinker within the thought itself, offers us a broad spectrum of ways to think alienation.

SUGGESTED VIEWING The divided self With Roger Penrose, Jack Symes, Sam Harris, Sophie Scott

Let’s first take a step back to appreciate the etymological and historical perspectives. The word alienation, in its root (alius), denotes becoming-other. It initially had a legal meaning, the transfer of property rights to another person, but by the 17th century, it came to refer to estrangement from one’s mental faculties. For example, in French, the word aliéné was used to designate a mentally ill patient.

___

In fact, as Derrida shows, Cartesian methodology, at its core, acknowledges the possibility of madness, and the claim “I think, therefore I am” is made in spite of it.

___

The term quickly acquired social connotations as well. Most famously, Marx spoke of the four-fold alienation of workers in industrialized societies. And if we cast our gaze on post-war French philosophy, we’ll discover a strong focus on becoming-other, whether in cases of pathology (analyzed through Freudian psychoanalysis) or in literature. In fact, all the basic words we use to conjure up our own perspectives – proper names, genders, social roles – inscribe themselves into the symbolic order of social relations. It’s hard to speak in one’s own name, precisely because the name is given by the Other. For instance, the French expression je m’appelle (literally: I call myself) expresses the desire of a subject to have power over their own name. Or, as the opening line of the great American novel reads: “Call me Ishmael.”

Join the conversation