The huge success of physics has led many to claim she is the queen of all sciences. According to this view, everything that takes place in the world could be explained, at least in principle, by the ultimate version of physics. But in truth, physics only reigns over small, easily modelled, subsections of reality. If we look at how science actually works when dealing with real-life, complex problems, we’ll see that physics plays only a small part, alongside a motley assembly of other natural and social sciences, engineering, and other disciplines, working together. The world is beautifully dappled, and requires a dappled science to explain it, argues Nancy Cartwright.

Physics, they say, is queen of the sciences. But not like Queen Victoria, who controlled only about a quarter of the world’s land area. Rather it is supposed to be as extensive as the Biblical text represents the domain of Caesar Augustus:

And there went out from Caesar Augustus a decree that all the world should be taxed.

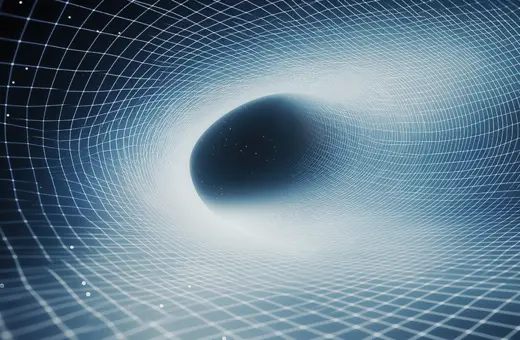

This image requires of course a physics far from what we have ever had or can envisage having for the foreseeable future. One that is internally consistent and coherent and whose successes at treating the world do not depend on choosing among or piecing together models and theories from different sub-disciplines in physics, but one whose models flow transparently and deductively from this one, unified, consistent theory.

SUGGESTED READING

There is no such thing as a scientific theory

By Steven French

SUGGESTED READING

There is no such thing as a scientific theory

By Steven French

If physics is to have total dominion, she must not only help out with chemical bonding, signal transmission in neurons, the flow of petrol in a carburettor, and the like. She must be able in principle to entirely take over the disciplines that usually study these things, to explain and predict the rise in teenage pregnancies, the current level of inflation, the Protestant Reformation, and the fate of migrants crossing the channel. Plus, she must be able to get me off the hook for shouting at my daughter: after all, I was just obeying the laws of physics.

___

Physics as queen is a tall order, and the world she would rule is altogether unlike the one we experience. Why then believe this physics is possible, even if we only mean ‘possible in principle’?

___

The idea of physics as queen of all that happens has powerful implications about just what the world we live in must be like. It must be a world made up entirely of the basic entities of physics—fundamental particles, curved space-time and the like — entities that have only the mathematical features that physics equations describe, features that often have no names of their own other than the names of the mathematical objects that are supposed to represent them, like the “quantum state vector” and the “metric tensor” of general relativity. The world has to be that way since these are the kinds of features that physics can rule.

But this is a strange world, nothing like the one we live and move about in. It is a world devoid of all the colour, texture and emotion, all the unending variation and richness of the world we see when we open our eyes and that we have to negotiate our way through to live our daily lives.

Join the conversation