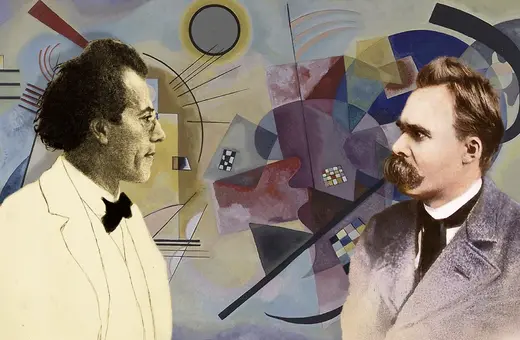

Nietzsche exalted Russia as a dark, patient, durable power that promised a lot more than what he saw as the weak and decaying Europe. The ideas driving Putin’s war against Ukraine are a lot more Nietzschean, and European, than many like to admit, argues John Milbank.

In one of his last works, The Anti-Christ, Nietzsche declares Russia to be ‘the only power that has durability in it, which can wait, which can still produce something…the antithesis of that pitiable European petty-state politics and nervousness, with which the foundation of the German Reich has entered its crucial phase…’. Earlier, in Beyond Good and Evil, Nietzsche had already made the same claim that only Russia possessed a real collective and institution-building will, whereas liberalism and democracy, which allow and celebrate passive weakness, were causing European institutions to disintegrate. These and other comments now seem prescient, demonstrating the Nietzschean roots of Putin’s ideology.

One of the things Nietzsche draws attention to is Russia’s different timescale, its ‘patience’ that derives from ‘a power to will that has been stored and accumulated for ages’. He then suggests that a weakening of this power, which ultimately threatens Western Europe, would require more than just a defeat of Russia in India and ‘complications in Asia’. It would also need ‘an atomisation of the [Russian] empire into many small bodies and above all the introduction of parliamentarian nonsense, including the compulsion for everyone to read his newspaper while eating his breakfast’.

Today these observations immediately strike us as all too pertinent. We can no longer assume that the sovereign, independent and democratic nation-state is the ‘end of history’, or that empires of various sorts are bound to decline. If Russia looks like a lumbering and wounded monster, then, equally, the West seems to be facing acute cultural division and a decline in the effectiveness of its public sphere. Which is the more fatal decadence?

SUGGESTED READING

The philosophers behind Putin

By Paul Robinson

SUGGESTED READING

The philosophers behind Putin

By Paul Robinson

As a European himself, Nietzsche certainly did not face the prospect of an ultimate Russian triumph with equanimity. But he thought that it could only be resisted if Europe itself moved from competing nation-state politics to become ‘equally threatening’ by ‘fusing into a single will’ which one has to mean an imperial will. It is in this sense that Nietzsche was indeed not a proto-Nazi, even if his prejudices operated at a more European level and demanded the emergence of something like a more ‘spiritual’, armed, and authoritarian European Union.

On the other hand, Nietzsche also viewed the rise of Russia with a certain exaltation and glee. From the beginning to the end of his philosophy, he argued that the real high-points of the European past -- Greece of the Tragic era, Imperial Rome, the Renaissance -- had involved a certain tempered infusion of what he regarded as the barbaric, orgiastic, and unremittingly stern and forceful elements of the Asiatic. From that perspective, Russia is not just a menace to Europe but offers it something that it needs if it is to revive. This ‘something’ can be found in what Nietzsche found valuable in the novels of Dostoevsky – and that was certainly not their Christian dimension.

___

One of the things Nietzsche draws attention to is Russia’s different timescale, its ‘patience’ that derives from ‘a power to will that has been stored and accumulated for ages’

___

Join the conversation