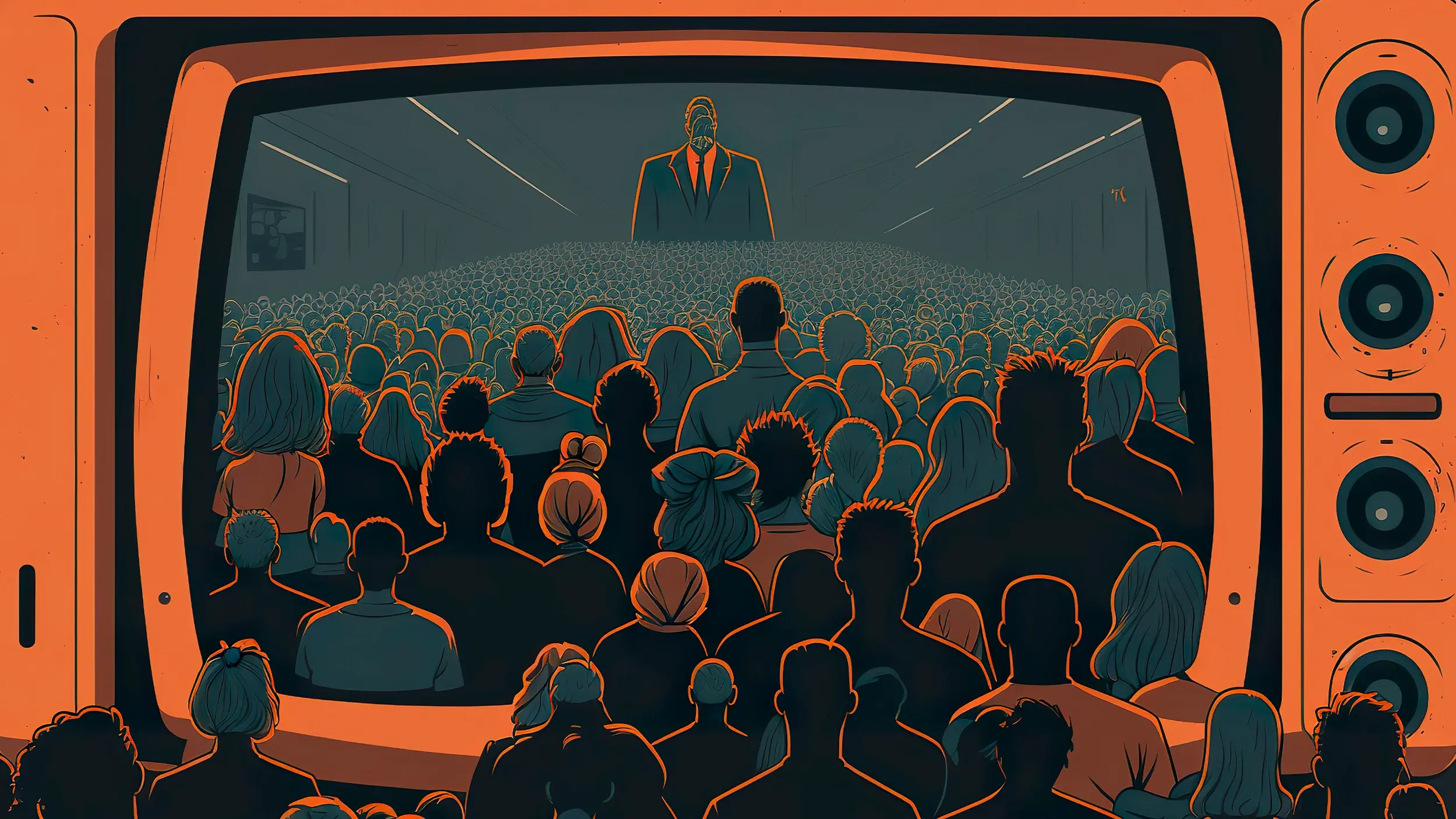

Attention is the basis of our free will, allowing us to direct our minds as we choose. Technology poses a threat to this individual agency, writes Carolyn Dicey Jennings, but may also yield new rewards. Social media harnesses our attention for incentives that aren’t our own, sublimating it into the interests of the group. We are trading our individual power for collective power, and we need to understand the risks and benefits of doing this.

Attention is the source of our power. Before every choice and action, you first organize your world through attention—your priorities push some things closer to the center, other things to the sidelines. The center then shapes your thoughts, choices, and behaviors. Without this ability we would not have agency or autonomy—we wouldn't be selves. But we are more than selves. Our priorities and projects are bound up with others, whose interests shift our own. Our evolutionary history adds more pushing and pulling to this mix, sometimes against our values. All of these influences are woven into a single landscape, controlling our thoughts and actions.

___

The question is: where does our power go, and will it be used to our benefit?

___

Recent technologies change this landscape by favoring what is predictable—our biological propensities and social instincts—and diminishing our role as individuals. The question is: where does our power go, and will it be used to our benefit? The collective power enabled by these technologies comes with new risks and rewards, and it is worth considering how we can best leverage it.

Each of us is born into a world of influences, biological and social. Philosophers and scientists have argued for thousands of years about whether we have any independence from these influences—whether we are “free” to set our own path. While this idea is intuitive, a coherent, scientifically sound explanation of free agency is an ongoing challenge. Many famous philosophers and scientists have argued that it is impossible, seeing room only for a reductive and deterministic worldview.

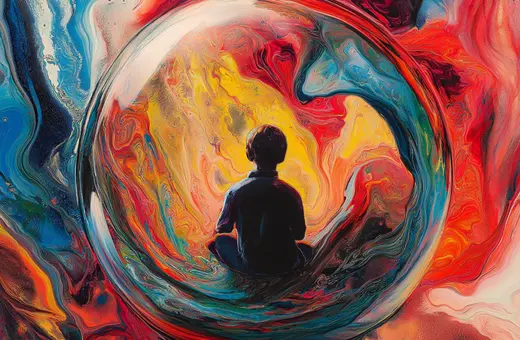

Enter attention. Attention is how biological, limited creatures like ourselves favor some stimuli and responses over others. Decades ago, philosophers introduced the idea that our freedom comes from self-regulation, but left it unclear how to square this with the reductive and deterministic worldview without losing the true sense of “freedom.” I have used research on attention from psychology and neuroscience to demonstrate the possibility of a deeper form of freedom.

The idea is this: your interests are initially provided to you by evolution and early upbringing (“bottom-up” influences), but you can start to control those interests through attention (“top-down”). Namely, when your interests are in conflict, you can, with effort, redistribute resources and “press the scales” to favor one interest a bit more. Your ability to do so is a non-reductive power that is not solely determined by your neurons or genes. Thus, through attention you can direct and shape your own mind, the basis of free agency.

Join the conversation