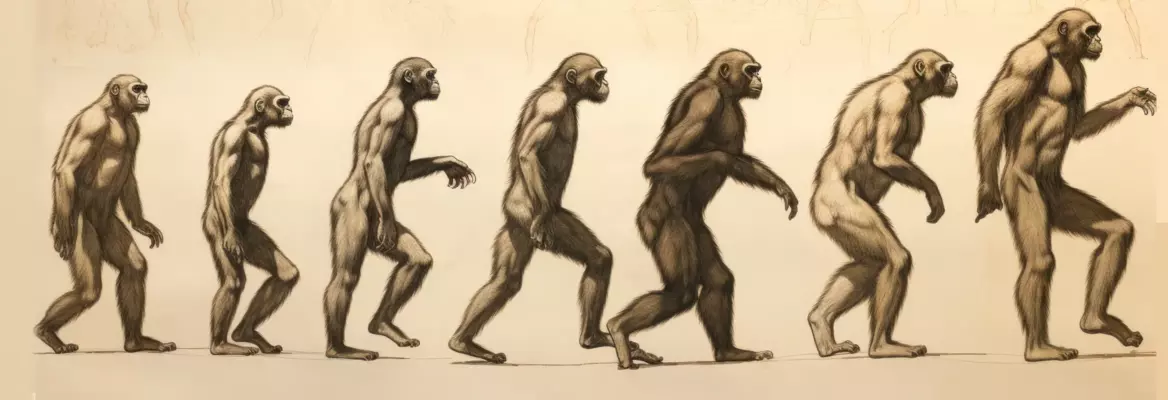

The idea that evolution is a linear progression from "ape to angel" is flawed, argues Guy P. Harrison. Five decades after the discovery of Lucy, the fossil of one of the most ancient hominids ever discovered, why should we still be studying her? Lucy offers invaluable insights into our origins, highlighting Africa's central role and showing that bipedalism preceded brain expansion, reminding us that humanity is not the pinnacle of evolutionary progress.

Five decades after the 1974 discovery of Lucy, the most famous fossils of all time, it is fair to ask, So what? Why should anyone still care? Hasn’t she been scrutinized, popularized, and mythologized enough? What’s left beyond scientific minutiae and fodder for academic journals? There have been remarkable achievements in many fields of science since that November day when paleoanthropologist Donald Johanson spotted a three-million-year-old right ulna (lower-arm bone) that had been exposed by erosion in Ethiopia’s Afar region. Moreover, with climate change, biodiversity loss, nuclear-war risk, and the possible emergence of an artificial superintelligence, don’t we have more pressing concerns? What can the stone echoes of one long-dead Australopithecus afarensis possibly tell us that holds any relevance today? Plenty, it turns out.

The discovery had immediate scientific value in the 1970s because of the age (3.18 million years) and how relatively intact and numerous the fossils were (approximately 40 percent of a complete skeleton). Lucy showed us what ancestors just outside the outermost edge of our genus really looked like and how they most likely behaved and survived. She further solidified Africa as central to the human past and revealed that bipedalism came before larger brains. Lucy helped us understand that the evolution of life, including us, is not a ladder or linear path of progress from “ape to angel”. She also presents a subtle warning. Nature doesn’t care. There are no guarantees. Extinction can happen, even to the brightest species of the day.

The name Lucy was inspired by the Beatles’ hit song “Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds” that played in the discoverers’ field camp during celebrations. She has other names: “Heelomali” (The Afar peoples’ name for her that means “She is special”); Dinkʼinesh (Ethiopian/Amharic for “you are marvelous”); and AL 288-1 (her official science ID). Going in the other direction, the fossils inspired NASA to name one of its spacecraft “Lucy”. It is on a 12-year exploratory mission near Jupiter and an asteroid it discovered in 2023 was named “Dinkinesh”.

___

It is not necessarily doomsday paranoia to worry about Homo sapiens’ chances over the next thousand years, or even the next hundred.

___

A few million and fifty years on, it is clear that neither the Pliocene nor modern museums can contain Lucy. She continues to be a source of pride for Ethiopians and other Africans, showing up on stamps, billboards, and in tourism marketing campaigns. Though distanced from us by the subjective borders of taxonomy and objective measure of years, the idea of Lucy remains close and relevant to modern humanity. She is a thundering emphasis to how ancient, complicated, and exciting the human-origin story is.

Join the conversation