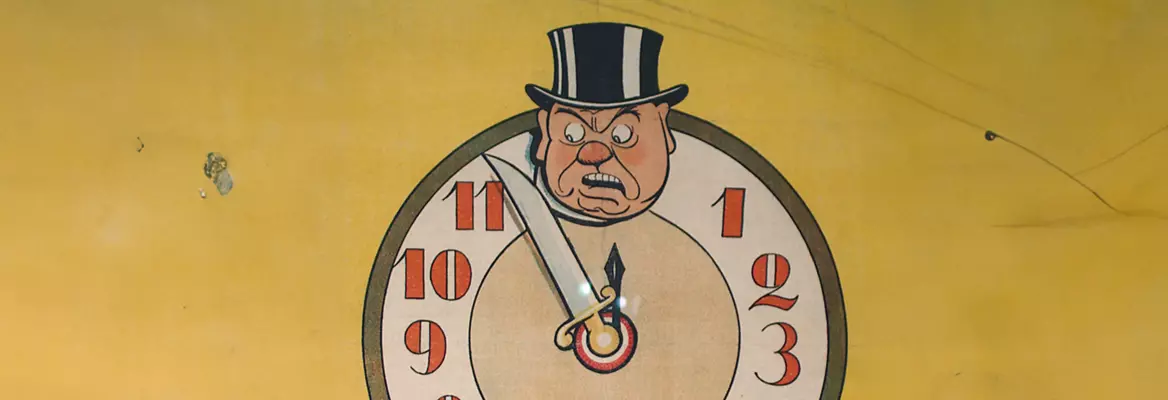

Time is our most precious asset, but it is increasingly the reserve of the privileged few. Arguing that the dichotomy of “work” and “leisure” no longer applies in the modern age, Guy Standing proposes a new progressive politics of time, seeking to move beyond regulations on labour hours and to combat the rise of the panoptican state.

Too often, politicians, commentators and social scientists divide time into a dualism of ‘work’ and ‘leisure’, with work defined as what is done for an income, in ‘jobs’, while leisure is whatever time exists outside of this. So, if weekly hours in a job go down, leisure is automatically presumed to go up. This presumption is wrong. It ignores all the unpaid work that people choose to do, such as care for their children or elderly relatives, or work in the community. More importantly, it ignores the unpaid work that people are obliged to do, by employers or by the state, that is driving the growing inequality of time.

In discussing this inequality, it is useful to recall that the ancient Greeks divided time into not two but five types of activity – labour, work, recreation, leisure (schole) and idleness (aergia). Schole involved education and public participation in the polis, that is, political activity. This was separated from recreation, such as exercise and entertainment. Aergia was regarded by Aristotle as a vital use of time, encompassing contemplation. This was later captured by Cato’s aphorism, ‘Never is a man more active than when he is doing nothing.’

The ancient Greeks also distinguished between ‘work’ and ‘labour’. Citizens did not do labour. The production of goods and most services was left to slaves, and to labourers and artisans as their means of gaining subsistence. However, citizens did do ‘work’ that included care for family members, study and education, military training, and creative activities. Labour, as is clear from its etymological roots, was seen as onerous, deforming the body and mind. And those doing labour were considered to lack the time to educate themselves on political affairs, so were denied citizenship and the rights that went with it.

___

The late twentieth century saw the emergence of a tertiary time regime. Instead of blocks of time and fixed workplaces, boundaries between all types of activity began to blur.

___

Armed with this framework of time uses, and abstracting from the specific hierarchical and patriarchal nature of ancient Greek society, we can trace history through three overlapping time regimes. The agrarian time regime, which lasted into the Middle Ages, was the age of ‘commoning’, when the working classes struggled to pursue subsistence in the commons and avoid labour for a feudal lord. This way of life was legitimised by the Charter of the Forest, the most subversive constitutional document in history, sealed alongside Magna Carta in 1217, which upheld commoners’ rights against the monarch’s unlawful enclosure of the commons.

However, the rising capitalist class wished to force more people to do more labour for employers and landlords. Besides curtailing commoners’ access through subsequent enclosures of land, water and other resources, they resorted to coercion, culminating in the Vagabondage Acts of the mid-sixteenth century. Any poor person found not doing labour was branded with a V for a first offence and hanged for a second.

Join the conversation