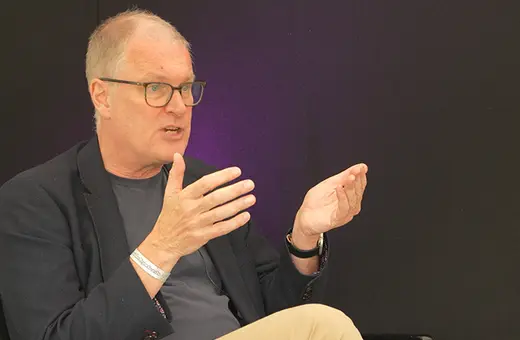

What are climate tipping points and how were they discovered? Could positive social tipping points be key to the challenges we now face? Tim Lenton, who pioneered the science of climate tipping points looks back at their history and at what lies ahead for planet earth.

A tipping point is where a small change makes a big difference to a system. They are an example of ‘non-linearity’ – output is not proportional to input. Non-linearity can happen when strongly self-reinforcing feedbacks are present. The initial small change follows a closed-loop of causality that feeds back to amplify it. Then the now larger change goes around the loop and gets further amplified, and so on.

For example, as the Arctic sea-ice melts it exposes a much darker ocean surface that absorbs more sunlight, warming the region and melting more sea-ice, which warms things further, and so on. Or when Greta Thunberg started her school strike in front of the Swedish parliament, she made it incrementally easier for the next person to join her, who made it slightly easier for the next person, and so on.

Mathematically both are examples of ‘positive’ feedback – but the emotional meaning may differ from the mathematical one. Loss of the sea-ice is a bad thing. The School Strike for Climate is a good thing (for me at least). In both cases, the amplification can be strong enough to propel change from one state (ice cover/no protest) to another (ocean cover/mass protest). The point where that happens – if it happens – is the tipping point.

The corresponding mathematical concept of a ‘bifurcation’ was introduced by Henri Poincaré in 1885, and the language of ‘tip[ping] point’ first emerged in a social science context in 1957. Meteorologists started studying bifurcations in the climate – including those leading to deterministic chaos – in the 1960s. But it was not until Malcolm Gladwell popularised the term ‘tipping point’ in his 2000 book that the language of ‘tipping points’ started to be used to describe abrupt changes in the climate system.

In the mid-2000s, John Schellnhuber and I led a systematic identification of what we called the ‘tipping elements’ in the climate system – those parts of the planet that could be pushed past a tipping point by human activities this century. We drew on three sources of evidence: firstly, well-known abrupt climate changes in Earth’s recent past. Secondly, abrupt shifts occurred in some climate model projections of the future. Thirdly, our fundamental understanding of feedbacks within the climate system. A workshop with colleagues helped refine the list. The resulting map identified around ten potential climate tipping points.

"We were derided by other colleagues. The suggestion that human activities could trigger future climate tipping points was portrayed as alarmist"

We were derided by other colleagues. The suggestion that human activities could trigger future climate tipping points was portrayed as alarmist – and much less certain than that human-caused increases in the concentrations of greenhouse gases are causing global warming. Given how long it was taking to get that basic 19th century physics widely accepted – in the face of powerful vested interests – our detractors can be forgiven. Except that science is meant to be about the evidence and already in the 2000s we were observing accelerating Arctic sea-ice retreat and accelerating melt of the Greenland ice sheet (to name but two causes for alarm).

Join the conversation