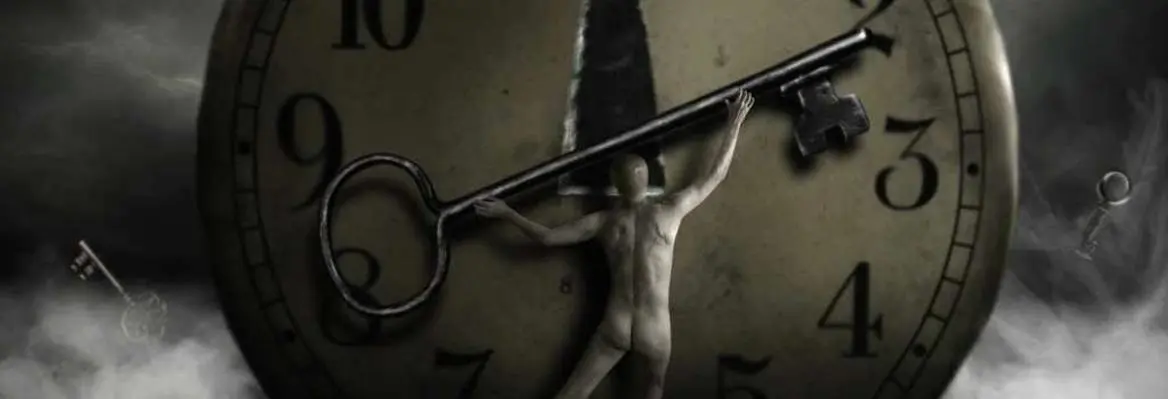

Human life is finite. It consists of time – hours, minutes, seconds – ticking away. We are both conscious of time and in denial of its meaning. We often hurry through activity-packed days, rushing from one commitment to another. We yearn for the end of the school year, the end of winter, the end of a busy period at work. But we also hate to think about growing old, dwindling away and eventually dying. We exist in time, but it is also that which measures the passing of our days. It is the events which punctuate human life – big birthdays, finishing school, having children – that arouse our consciousness of time. They make us pause and evaluate our life: where we got to, where we’d like to be, and the often bewildering distance between the two. As Marilyn Monroe put it in Some Like it Hot, “A quarter of a century makes a girl think!”.

So time rushes onwards, bringing new events and experiences in its fold, but it also, with every passing moment, brings us closer to death. And because we accept the former and deny the latter, having a deep understanding of time can be painful. For 20th century philosopher Martin Heidigger, we are nothing but a “being towards death”, an arch stretching from our moment of conception to our moment of demise. Being is inextricably linked to ceasing to be; death is the condition of life. In order to live one must be capable of dying. Even though we now have medical technologies that may keep us alive much longer than previously, nonetheless, there is something strangely profound in the fact that mortality is such a central aspect of human life as it is today.

Heidegger battled against the “tranquillisation” of death that social norms and public “idle talk” promote: “We all die in the end, but not right now. Right now I’m alive, and death has nothing to do with me.” Heidegger called this attitude inauthentic. For him, the deliberate forgetfulness of death marked a human life that is crushed by the force of the “they”, incapable of independent thought, and existentially impoverished. If I do not grasp my finitude, the weightiness of each moment, lived once, only once, bypasses me. If, on the other hand, I face my finitude with resoluteness, I can authentically engage with my existence, because I have grasped it as finite.

Every moment, for Heidegger, encapsulates freedom and choice. Every moment opens up possibilities which I may seize or discard, act on or reject. And this existential openness, this freedom characterises human life. But it comes at a cost. It demands of us to refuse to repress or walk away from our future death. In this sense, death is not something that is far away in the future – some remote, gentle going into the night. Death makes every moment precious, dictating its unrepeatability. And as such it is infused into every present moment, every “now”. The present moment is our only moment, we might say. It is such only because of death.

What Death Tells Us About Life

We can't understand life until we understand death

Want to continue reading?

Get unlimited access to insights from the world's leading thinkers.

Browse our subscription plans and subscribe to read more.

Already a subscriber? Log in

Henry an 15 March 2021

Havi Carel in this discussion explains about death and life of humans. It only consists of time hours and minutes. Time rushes onward and we do not even realize. The https://www.edugeeksclub.com/buy-research-papers/ is one of authentic approach for writing service. You can check for more info.

Alex Juvion 28 July 2020

You did great job to written and shared such an unique as well as knowledgeable blog on this website. I am excited to read future blogs.

Regards, Alex. Senior assignment writer http://www.qualityassignment.co.uk/services/assignment-writers/ in Quality Assignment’s writer team.

Join the conversation