A well-known May 1968 slogan reads: "Be realistic, demand the impossible!" Is that just an affected Parisian provocation, or does it contain a useful insight? Suppose you've every reason to believe that your political dreams are unachievable. Your ideals yield prescriptions--things we ought to try to bring about--that just won't happen. Not now, not anytime in the foreseeable future. Or maybe your ideals don't even lead to prescriptions: perhaps all they tell you is that the status quo is rotten and ought to be replaced by something else, though you don't know what. But the question is, as they say, academic, since the revolution isn't happening anyway. If that's what your political ideals tell you, what should you do about it? And does thinking in that way make you a political failure?

To avoid answering the latter question in the affirmative, most philosophers would answer the former in one out of two ways. The first answer is to say that, well, you should revise your ideals, for they fail to latch onto politics in the right way. The second answer tells you to think of your ideals as merely regulative: they give you an indication of a general direction, rather than a political programme. Radicals are unlikely to be happy with either answer. The first one is just an encouragement to abandon radicalism in the face of the political odds. The second one makes it hard to envision the ultimate political import of one's radicalism: is my radical politics just a fantastical wish list? Yet those two answers may not exhaust the options available to us. Theodor W. Adorno, the stern patriarch of post-war Frankfurt School critical theory can provide us with a third answer, and one that's more appealing to radicals of an uncompromising sort. Or, some would say, to academic solipsists who don't want to get their hands dirty with real politics -- you be the judge.

___

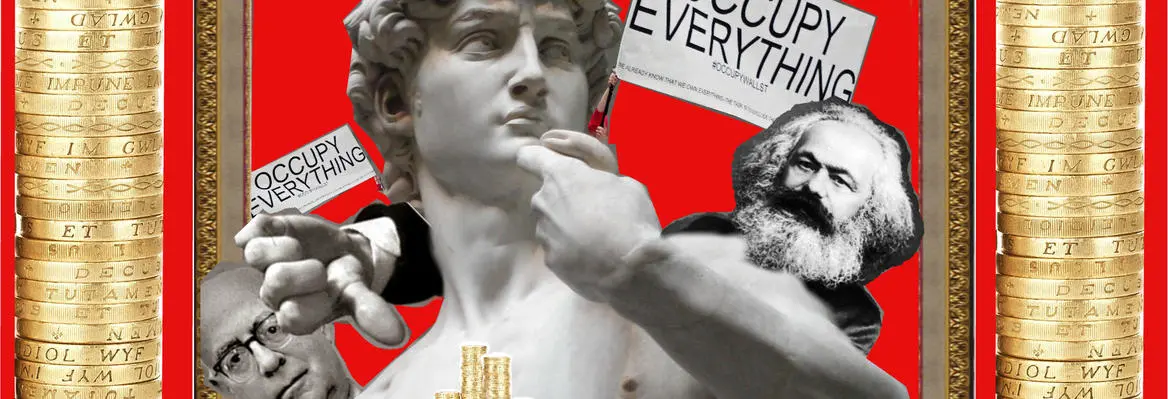

"Sculpture consists in the removal of material — Michelangelo ably chips away at a block of Carrara marble until David takes shape."

___

Adorno is known for his "negativistic" approach to social criticism. The rough idea is that the social critic need not (always) come up with a feasible plan for how to change things. She can just complain, as it were, and not be a failure for that. But how would that work? And does this sort of social critic become an unmoored dreamer or can she retain, in some non-trivial sense, a realistic grasp of the hard facts of politics?

Adorno's answer is best understood within the context of his Marxism, and specifically an internal debate within Marxism on normative theory - does Marx, or the best version of his view, put forward a set of prescriptions telling us to bring about socialism and communism, or does he rather limit himself to causal claims about why society works in the way that it does, and under what conditions it will be transformed by a revolution?

We can begin to understand Adorno's position if we think of it as a middle ground between those two options, the normative and the anti-normative reading of Marx. Adorno’s critical theory is a normative approach, but one that eschews the direct advocacy of a socialist programme, and limits itself to negative critique.

An analogy with sculpture might help here. According to a traditional definition, sculpture consists in the removal of material — Michelangelo ably chips away at a block of Carrara marble until David takes shape.

Join the conversation