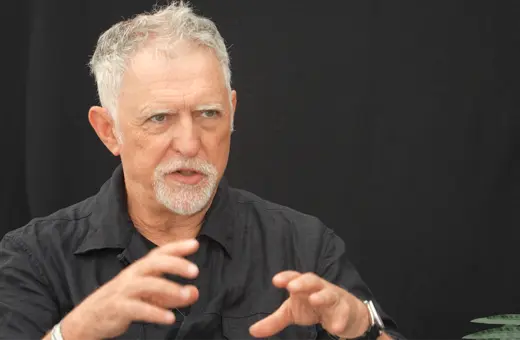

The claim that reality’s fundamental building blocks are conscious can seem to challenge what physics tells us the world is like. It’s no surprise then to find prominent physicists arguing that panpsychism is incompatible with physics, and therefore false. But that would be to misunderstand panpsychism: It’s not a competing scientific theory, but a philosophical interpretation of the claims of physics, argues Philip Goff.

Sean Carroll will debate this issue with Philip Goff and Keith Frankish live on the 'Mind Chat', YouTube channel 11th November, 2pm UK time: https://www.youtube.com/c/MindChat

Panpsychism is the view that consciousness is a fundamental and ubiquitous feature of the physical world. It is the view that the basic building blocks of the physical universe – perhaps fundamental particles – have incredibly simple forms of experience, and that the very sophisticated experience of the human or animal brain is rooted in, derived from, more rudimentary forms of experience at the level of basic physics. Panpsychism has received a lot of attention of late. The world of academic philosophy has been rocked by the conversion of one of the most influential materialists of the last thirty years, Michael Tye, to a form of panpsychism (panprotopsychism) in his latest book. And the main annual UK philosophy conference held a plenary panel on panpsychism this year for the first time in its history.

Much of the attention has been critical, which is as it should be when it comes to matters on which there is little consensus. Among the recent critics are two leading theoretical physicists: Sabine Hossenfelder and Sean Carroll, who argue that panpsychism is incompatible with what fundamental physics tells us about the building blocks of the universe. However, these objections rely on a misunderstanding of what panpsychism is. Panpsychism is not a scientific theory in competition with physics, and therefore not incompatible with it. It’s rather a philosophical interpretation of the claims of physics.

Physicists against panpsychism

Hossenfelder has argued that there is a clash between panpsychism and the standard model of particle physics, our best physical theory of the 25 known fundamental particles. The standard model characterises particles in terms of their physical properties – such as mass, spin, and charge – and makes precise predictions on that basis. Hossenfelder’s thought is that if, in addition to their physical properties, particles also had non-physical consciousness properties, these latter properties would presumably have an impact on the behaviour of the particles, resulting in predictions different from those of the standard model (as the standard model makes its predictions solely on the basis of the particles’ physical properties). The predictions of the standard model are very well-confirmed, and so, according to Hossenfelder, we ought to reject panpsychism.

Hossenfelder has argued that there is a clash between panpsychism and the standard model of particle physics, our best physical theory of the 25 known fundamental particles.

Join the conversation