Democracy has achieved some incredible things, making our societies more equal and just. But in recent years rather than being an efficient mechanism for collective decision-making and progress, democracy seems to be fueling discord, division, and distrust of the other side. Do away with elections and democracy itself might be saved, argues Alexander Guerrero.

Elections are not magical, but they can seem that way. The last 200 years have seen electoral democracy as the ascendant, most successful kind of political system the world over. Electoral systems have improved internally as slavery, colonialism, racist and sexist discrimination, and disenfranchisement have gradually if not entirely been challenged and eradicated. But we are starting to see new trouble. In many democratic political communities, the leading story is one of division, rage, and irrationality. It is hard to imagine a path together, forward, in response to the urgent challenges we face. Elections are not magical. They don’t automatically make everything better. They only work well under specific social conditions. And if those conditions do not obtain, elections can actually make things worse.

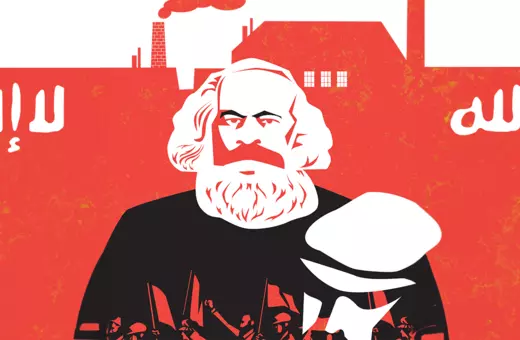

As a teenager attending public schools in the United States, I was taught that our political system was the best and only legitimate form of government. I was also taught almost nothing else about the system. There was a Constitution, a Bill of Rights, three branches, some checks and balances (no one knew why the branches would check each other), elections, and freedom. Our system was considered so much better, that I was taught nothing about other democratic systems. The options seemed to be: this exact thing we have, some crazy king, or a communist dictator. My education was not unusual in this regard. Many of us live in political communities with stunted political imaginations and limited knowledge of how political systems work. That makes it hard when this apparently magical thing—electoral democracy—is not working well. It might seem that we don’t have better options. But we do.

Elections are not magical. They don’t automatically make everything better. They only work well under specific social conditions.

If we have a commitment to work together to solve problems, deep attachments and real affection, a common overarching cause, and basic, unshakable respect for each other, then taking a vote and going with the majority view can be an excellent way of working together, even in the face of disagreement. But if we do not have those things, elections are dangerously efficient ways of dividing us into groups, intensifying those divisions, and encouraging us to hate those on the other side.

The most important law in many democracies today was not passed by a legislature. In electoral systems in which one person will be elected to represent a district and the person elected is simply the person with the most votes, there will be two dominant political parties. This is Duverger’s law, proposed in 1954 by the social scientist Maurice Duverger. The precise character of the parties might change over time, but there will generally be two stable, dominant political parties. So, elections through systems like those found in the US, UK, Canada, and elsewhere will tend to result in two dominant political parties.

A significant part of our identity is connected to membership in our group and favorable bias towards it. We create these ingroups and outgroups readily and can do so on the basis of arbitrary and even invented characteristics.

Join the conversation