Modern society prizes hope and activism, treating optimism as a moral ideal and pessimism as a flaw. Drawing on Buddhist thought and contemporary philosophy, Nottingham philosopher Ian James Kidd challenges this cultural habit, inviting us to explore forms of pessimism that resist despair, without collapsing into false hope.

A curious feature of pessimism is that there are many reasons to be pessimistic and yet many people condemn being pessimistic. It only helps a little to point out that pessimism can apply to all sorts of things. I could be pessimistic about my meeting this afternoon, my financial future, the prospects for peace in the Middle East, or the prospects for humankind surviving into the next century. This includes specific and general concerns (the meeting; humankind), short- and long-term concerns (this afternoon; the 22nd century), and the different sorts of concerns (financial; existential). In these examples, we also see different grounds for pessimism – bad prior experience, inferences from the historical record, sober reflection on human nature, and so on. In some cases, I can also take action, doing things to try to change the outcome for the better – maybe going into the meeting with a “can-do” attitude. In other cases, the scope for my taking any meaningful action is zero.

Our everyday talk about pessimism, then, disguises all sorts of differences and difficulties. There are three important issues to consider. First, content—what, exactly, are we being pessimistic about? I recently asked a friend, a self-described “uber-pessimist,” what exactly she as pessimistic about. Her answer—“Absolutely everything!”—was concise but unhelpful. All but the deepest pessimists tend to think some things are better and some things might be improved. Second, justification—how does one justify pessimistic claims? What kinds of reasons and evidence are at work? Past experience tells me this afternoon’s meeting will be a waste of time. Justifying my pessimism about peace in the Middle East and the future of humankind, though, are different matters. History, sociology, political theory, philosophical reflection, and a judicious geopolitical understanding would be needed to justify those claims.

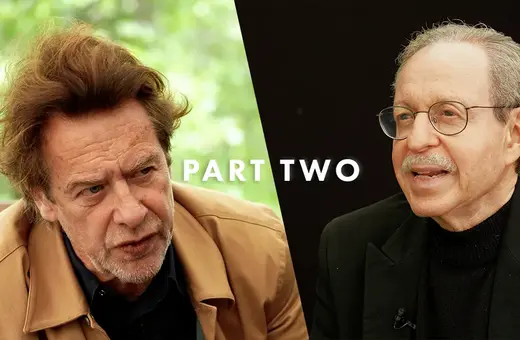

The third difficulty for pessimists is a practical one: what are the implications of one’s pessimism for one’s life? Announcing the conviction that “the world is fundamentally flawed” automatically poses the question of how to live in such a world. Of course, much depends on the content of one’s pessimism. Unfortunately, there is a tendency to focus on the most extreme, dramatic implications —like advocating the extinction of humankind, or, closely related, the anti-natalist proposal that we voluntarily cease procreating to gradually bring the human population down to zero. While these options shouldn’t be dismissed, we should emphasise other ways of being a pessimist. In a recent book, the pessimistic philosopher, David E. Cooper argues for a kind of “quietism”—accepting with a mood of disquiet the dreadfulness of human life, but still working to live virtuously and tranquilly within its constraints. Abandoning ambitious conceits to be able to rectify the world, seeking “refuge” in natural places, cultivating a more modest sense of the good one can do—these are cooler ways of living out a pessimistic vision of life, free of extreme and nihilistic ambitions.

Join the conversation