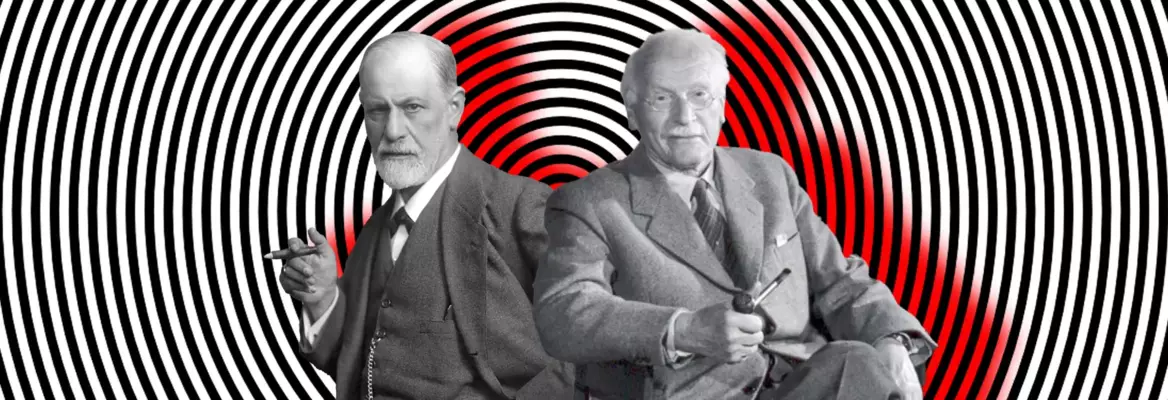

Freud and Jung offered two distinctive ideas on the development of the self: one shaped by early experience and the other by the forces of nature imprinted in the archetypes of the collective unconscious. For Freud, trauma can be explained by childhood experience, while Jung looked to the wider collective. But, Andrew Samuels argues, we are political animals. The political world affects the psyche much more than is usually given credit for, and while we should use the ideas of both Freud and Jung, we must also move beyond them.

Where does psychological distress come from? Why do so many people have ‘emotional issues’? What should be done, and by whom? These contemporary questions are themselves the end results of a century and a half of systematic enquiry embracing – but not culminating in – the work of Freud and Jung.

Those two patriarchs of psychology and psychotherapy represent two poles of the nature-nurture debate, though it is not really as neatly bifurcated as that. Freud’s work on the aetiology of neurosis in family dynamics, in which reconstructing the past history is central, is epistemologically different from that of Jung. Where Freud looked for causal chains in personal history, Jung looked to universal patterns in what we could call the constitutional personality; what is inborn, the acorn from which the tree develops.

SUGGESTED READING

You are not one Self, you are many

By Joanna Nadin

SUGGESTED READING

You are not one Self, you are many

By Joanna Nadin

The archetypes of the collective unconscious – the layer of the unconscious mind containing shared psychological patterns, or archetypes – are, assuming one agrees that they exist at all, rooted in the body. In many ways, Jung was the first neuropsychologist. His insight that these patterns that characterise human experience might have corresponding structures in the brain anticipated the key interests of today’s neuroscience.

Freud’s interests were in the relationship between a person and their father and mother, and in the ways in which the parents relate according to the child’s experience of it. While some of his ideas seem extreme, and they are irradiated with sexuality, this family-in-the-past approach to people’s problems in the present has endured and remains a dominant model today. Jung did not ignore the family, but he was much more interested in the ways in which what you could call the problems of humanity made their presence known in the individual. Both were interested in dreams, and both have a lot to say about gender. But these different approaches to the psyche suggest fundamentally different ways of understanding distress - as either wounds from personal history or as disruptions to archetypal patterns of development.

___

Many therapists report that their clients and patients are disturbed by the climate crisis as if it were an internal, personal and subjective matter. Which, in a way, it is.

___

These matters are relevant to a world in which ‘mental health’ and ‘mental illness’ are ubiquitous. But a third line of exploration is emerging, different from biological facts or personal dynamics. This third line is the ‘psychosocial’ one. The main idea is that the political, economic and social arrangements live vividly in the inner worlds of citizens. Indeed, the division between inner and outer is something that is being disputed by therapists of many persuasions.

Join the conversation