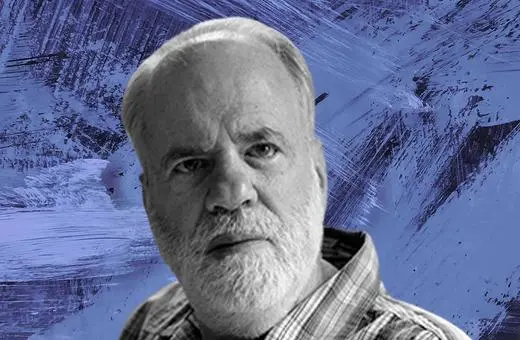

Language is the main tool we have to communicate to others our view of reality. We choose our words carefully to convey our perspective. But that perspective is itself already shaped by the language we use. Language therefore is far from an objective medium that simply reflects the way the world is. We create different worlds using different vocabularies, even though we are still constrained by a language-independent reality. If we assume its main aim is to reveal the truth, that makes language seem deeply flawed. But if we come to understand language as a tool for convincing and persuading other people, we can come to recognize its strengths, argues Nick Enfield.

When primate scientist John Gluck began his research career in the 1960s, he was taking new-born rhesus monkeys from their mothers and raising them alone in bare steel containers, to study the effects of social isolation. In time, he came to question why he was doing this, and would soon deeply regret the harm and suffering he had caused. In the midst of a successful scientific career, Gluck abandoned his research and applied himself instead to promoting animal welfare. With hindsight, he identified one factor of special importance in explaining how a good man can do bad things. That factor is language.

As a young scientist starting out, Gluck liked the language of the branch of psychology known as behaviourism because it signalled an intellectual stand. The behaviourist does not say that an animal is frightened, only that it is avoidant. He does not say that it is smart, only accurate. He does not say that the animal is hungry, only that it is food deprived or has a latency to consumption. That stand became part of Gluck’s identity within the culture of scientists doing animal experiments. By using the idiom of his teachers and peers, Gluck had elided—some might say erased—the inner experiences of the animals he worked with. “If you must sanitize the language that is used to describe the procedures in regular use,” Gluck wrote, “you have entered morally perilous territory.”

___

Just as language cannot create physical reality, it cannot merely reflect physical reality as it is.

___

On his path into that perilous land, Gluck had exploited the power of language for two purposes. One was sense-making: to create a version of reality that cohered with his chosen purposes and actions. The other was rationalization: to provide justifications for those actions. When he came to understand the power of words in creating a world and defending it, John Gluck discovered something fundamental. Just as language cannot create physical reality, it cannot merely reflect physical reality as it is. It always imposes a doubly-subjective vision, consisting of the views encoded in the language being spoken and the view of the speaker who chooses the words being used. Language is shaped by our subjective, purpose-calibrated view of reality. And in turn, our view of reality is shaped by language. Just as Gluck’s old worldview was enabled by the language he used, so too would language play a role in recasting that worldview, in bringing about his personal and professional redemption. Gluck’s story has a key insight: We create our worlds with the language we use.

Join the conversation