Traditionally, love is seen as a profound and enduring connection. Yet, as Lacan and Deleuze describe, love is also a mad compulsion where we throw ourselves repeatedly against the wall between self and other. Insofar as love is necessary, Sinan Richards writes, it lies in identifying and seeking this madness in each other, and embracing imperfection.

While writing The Dialectics of Love in Sartre and Lacan, I was living and teaching in Paris and would often travel to London by train to see friends and family. On one such trip, I was asked by a British Border Force agent at St Pancras International: 'What is it that you do, then?' When I explained that I was working on a book on Jean-Paul Sartre and Jacques Lacan and how love was impossible, the border guard retorted scornfully, 'That’s the problem with you academics – you spend so much time thinking that you can’t get on with it.' This exchange still makes me chuckle, because, although rude, what if he was right?

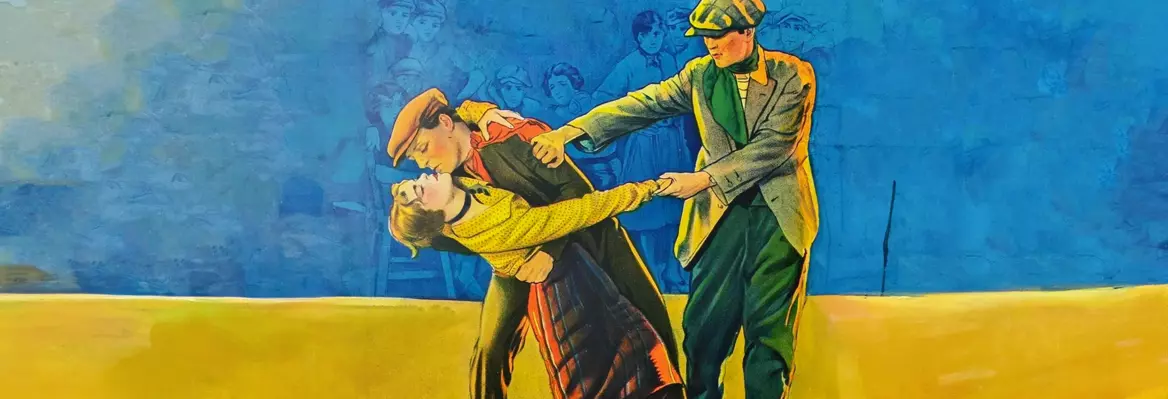

Between 1988 and 1989, while filming L'Abécédaire, Gilles Deleuze linked a fundamental aspect of love to madness. Deleuze says: ‘if you don’t get the little kernel of madness in someone, then you can’t love them. If you don’t seize their point of insanity, you fall short. The location of someone’s insanity is the source of all their charm.’ Deleuze is right: there is a remarkably close proximity between madness and love, and this was also true for Lacan.

___

We could even say that madness is love’s modus operandi.

___

For instance, consider how we tend to deploy metaphors of madness when we describe love: ‘crazy in love’; ‘madly in love’; or as Alain Badiou often puts it, how love requires a fall, ‘fall in love.’ We could even say that madness is love’s modus operandi. And, although we earnestly use these terms, all this seems rather paradoxical and counterintuitive when we stop and think about it. Why exactly would love be linked to madness? And why is love – in a sense – multiple? For example, we can all agree that there is a difference between ‘I love you’ and ‘love ya’. So, what’s the difference?

Join the conversation