We look to maps for guidance, helping us to navigate the world as effectively as possible. But are maps as neutral and objective as we think? Cultural geographer Mike Duggan argues that what goes on the map – and who decides – has a significant impact on our lives that we often don’t notice.

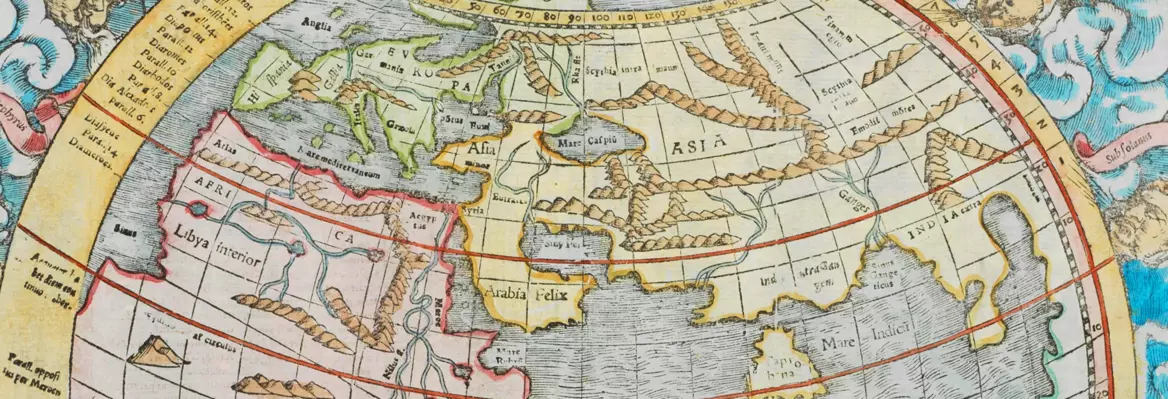

In the popular TV show The West Wing, White House Press Secretary C.J. Cregg and Deputy Chief of Staff Josh Lyman have their minds blown after it is revealed to them that maps can distort real geographies. After being shown a Gall-Peters projection map, where the map more accurately represents the real size of countries compared to the older and more popular Mercator projection map that we are all accustomed to, both are visibly dismayed at the notion that Greenland is not as big as they thought, actually fourteen times smaller than Africa despite appearing comparable, and that Germany was in simply the wrong place.

Maps claim to show a view from nowhere – an objective view of the world, and yet the Mercator projection is map with Europe at is centre and European interests at its heart. There is nothing natural about this perspective, but still it has become normalised.As philosopher Donna Haraway famously asserted, scientific claims, which include maps, are presented as if they are universal truths, rather than ‘situated knowledges’ produced by people who can only ever offer a partial view of the world. As mapping creeps into ever-increasing domains of human consciousness though our interfaces with map-enabled digital apps, we should be more mindful than ever that maps aren’t neutral. We should keep in mind that the Mercator projection is a product of western cartography, designed to amplify western power. It certainly does not represent how all people and cultures see the world.

SUGGESTED READING

Mapping the illusion of reality

By Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther

SUGGESTED READING

Mapping the illusion of reality

By Rasmus Grønfeldt Winther

The idea that maps reflect the world views of their makers – and in turn that maps have the power to shape public perception and opinion – was first laid bare by academics such as Brian Harley in the 1980s, who set the stage for a generation of ‘critical cartographers’ to unpick the details of maps and highlight where their power lies. Hundreds of studies have picked apart all kinds of maps to decode their power, from road, rail and street maps to urban plans, sea charts, strip maps, rock carvings and much more. Take street maps, for example, which claim to show us the details of our neighbourhoods. Studies show these are not objective; instead, they are carefully designed using colour, text, font, and symbols to give us the impression of neutrality. How parks are shown on these maps is a case in point. Painted in green, they appear inviting, neutral, and safe, when in fact parks are highly contested and dynamic spaces, changing depending on the time of day or year, or when different people occupy them. Street maps give us no indication of these dynamics, which are important factors people consider when going to a park.

___

The expertise of the cartographer lies in their ability to make selective representations of the world, not to reproduce it.

___

Join the conversation