Dealing with uncertainty is a part of human life. Since human cognitive abilities are not up to the task of elucidating reality, we might think that we are forever doomed to an epistemic prison. Clinging to the illusion of certainty in the form of a "faith" or a "conviction" is no real antidote either. But according to Bernard Reginster, Nietzsche thinks that uncertainty should be a cause for gratitude rather than nihilistic despair. Once we see curiosity as a desire for inquiry rather than certainty, then we can begin to see how uncertainty evokes attraction rather than aversion. The joy we experience when raising endless new questions is thus a reason to feel grateful, not distressed.

Nietzsche once observed that “there may actually be puritanical fanatics of conscience who prefer even a certain nothing to an uncertain something to lie down on—and die. But this is nihilism and the sign of a mortally weary soul” (Beyond Good and Evil, §10). It is easy enough to see why we desire certainty: it settles us, by making us know where we stand, and delivers us from paralyzing anxiety. And yet, Nietzsche argues, the single-minded hankering for it is a sign of nihilistic weariness. In one respect, it is easy to see why: the world is vast both in size and complexity, and human cognitive abilities are not equal to the task of elucidating it. There is, therefore, no hope for the human being ever to feel fully settled in it. From the perspective of an uncompromising desire for certainty, life in such a world is bound to cause distress and invite repudiation [1]. And fanatically clinging to the illusion of certainty, in the form of a “faith” or a “conviction,” is no real antidote to this nihilism for, as Nietzsche also observes, such clinging already reeks of desperation.

SUGGESTED READING

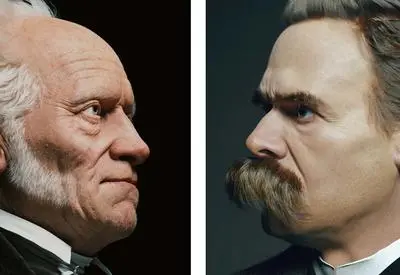

Schopenhauer vs Nietzsche: The meaning of suffering

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

SUGGESTED READING

Schopenhauer vs Nietzsche: The meaning of suffering

By Joshua Foa Dienstag

Nietzsche’s own antidote is “freedom of spirit (or mind),” which he describes as the condition of the individual who has managed to “take leave of all faith and every wish for certainty, being practiced in maintaining himself on insubstantial ropes and possibilities” (The Gay Science, §347). This characterization may suggest that the free spirit simply gives up on the quest for knowledge and resigns themselves to live in uncertainty. But such resignation would be less an antidote to nihilistic weariness than quiet acquiescence to it. On the contrary, the free spirit does not to abandon the quest for knowledge; they are a seeker after knowledge, animated by a true spirit of inquiry. Moreover, they find in the pursuit of knowledge a ground for affirming life, rather than repudiating it:

No, life has not disappointed me. On the contrary, I find it truer, more desirable and mysterious every year—ever since the day when the great liberator came to me: the idea that life could be an experiment of the seeker after knowledge … with this principle in one’s heart one can live not only boldly but even gaily, and laugh gaily, too. (ibid., §324)

Join the conversation