Isn’t it strange that we all have that little voice in our heads that continually deciphers good from evil? We often think our conscience is something close to a perfect moral compass. We only go morally astray when we don’t listen to it. But, Nietzsche argues, quite convincingly, certainly unsettlingly, that our conscience is just as fallible as the rest of us. Writes Christopher Janaway.

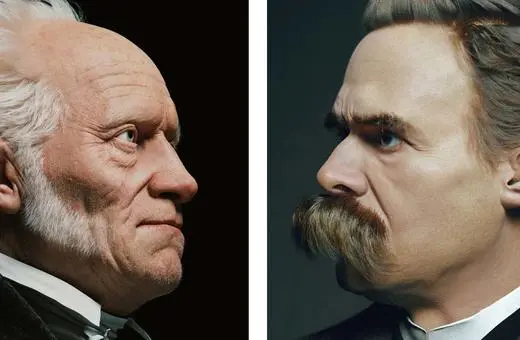

The twentieth-century French philosopher Paul Ricoeur described Friedrich Nietzsche as one of three modern ‘masters of suspicion’. The other two were Marx and Freud. All three encourage us to distrust the surface, the accepted face of things, and realise that something murkier is going on underneath. Like Marx, though for starkly opposite reasons, Nietzsche wants us to see ourselves as products of history in a way that could transform our culture’s future. Like Freud, he wants us to be suspicious of ourselves.

___

Nietzsche pleads for a ‘conscience behind your conscience’, an ‘intellectual conscience’.

___

Since ancient Greek times, ‘Know thyself’ has been a standard ethical maxim. But for Nietzsche knowing oneself is something rarely if ever achieved: we do not know, he says, how to observe ourselves. In his book The Gay Science — ‘gay’ meaning joyful — written in 1882, Nietzsche illustrates this claim through the notion of conscience. Why do you think that certain ways of behaving are right and others are wrong? ‘Because my conscience tells me so’, you might reply. Conscience is imagined as a kind of voice inside you that gives you instructions, telling you what you ought to do, as opposed to what you merely want to do. But what is this conscience? Where does it come from? Why and how do you listen to it? Nietzsche wants you to see that your conscience is not some autonomous source of authoritative judgement. Rather it is something that has come about through a network of causes, some of them with a long history, some of them internalised into your psyche, and that this psyche is a composite of competing non-rational forces, which he calls drives, inclinations, and aversions. The idea that there is a single, conscious, autonomous self in charge of your judgements, and that you hold your views for good reasons which this self owns and has worked out for itself, is all just a myth. Affective states such as fear, hatred, pride and shame, and more elusive, unnamable feelings of comfort or unease underly your conscious, seemingly rational responses.

Join the conversation