The living cell, once thought to be a precise molecular factory, is turning out to be more like an improvising jazz ensemble. The old dogma—one gene, one protein, one function—has collapsed. Molecular biologist Ewa Grzybowska argues that recent discoveries show that proteins can switch folds, shift shapes, or even remain gloriously unstructured, improvising their roles as they go. Genes are not blueprints but texts, open to continuous interpretation by cells. Life, it turns out, is not built like a machine but is instead fluid, improvisational, and brimming with creative possibility.

1. The old paradigms in biology

When Watson and Crick decoded DNA in 1953 and the mechanism of protein-making was discovered, we obtained an extraordinary tool to explain the inner workings of life. The basic principle of making one protein from one DNA template (gene) with the assistance of one messenger RNA (mRNA) and several well-defined amino-acid-transporting RNAs (tRNAs) was so successful that it has been enshrined in millions of textbooks and not questioned for a long time.

Ripples on this smooth surface appeared with the discovery of introns (non-coding parts, or sequences within genes that are not expressed in RNA, and so apparently don’t contribute to determining the protein) and splicing (basically, cutting-and-pasting the relevant parts of the genetic code to construct working mRNA and leaving behind introns). Later, alternative splicing was discovered, which directly contradicts the basic principle of one protein per gene, because it involves making several different working mRNAs from one gene. Several good explanations have been proposed for the role of splicing in general, and alternative splicing in particular, mainly focusing on regulatory functions, but a big question remained: why do all organisms, and especially more complex organisms, have this vast amount of non-coding DNA polluting their genomes?

We disregard what we do not understand, so people called this mysterious genetic material “junk DNA.” However, it should probably have been clear from the beginning that natural selection works at the level of the living cell and is both frighteningly effective and brutal. There is no place in the cellular economy for tolerating molecules that take a lot of energy to make and are of no use whatsoever. The functionality of this genetic material should have been considered axiomatic; we just had no idea what this elusive function might be.

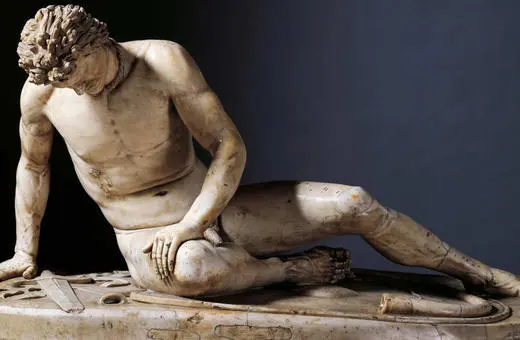

Proteins were considered the main output—the most important product (if not the only one)—of the genetic code. It was assumed that proteins are well ordered, have domains composed of defined elements of secondary structure (alpha-helices and beta-sheets), and that only these well-organized parts have important cellular functions. The poster example was always an enzyme: well structured, fitting to the substrate like a lock fits a key (the “Lock and Key Model” was proposed by Emil Fischer in 1894). It was also assumed that proteins have only one conformation (that is, one shape or structure), associated with one function. This is the one gene → one structure → one function paradigm.

___

We disregard what we do not understand, so people called this mysterious genetic material "junk DNA".

___

This linear, static, well-organized picture started to change in the second half of the twentieth century, and the change accelerated abruptly with the turn of the century.

2. The brave new world of non-coding RNA and intrinsic disorder

Join the conversation