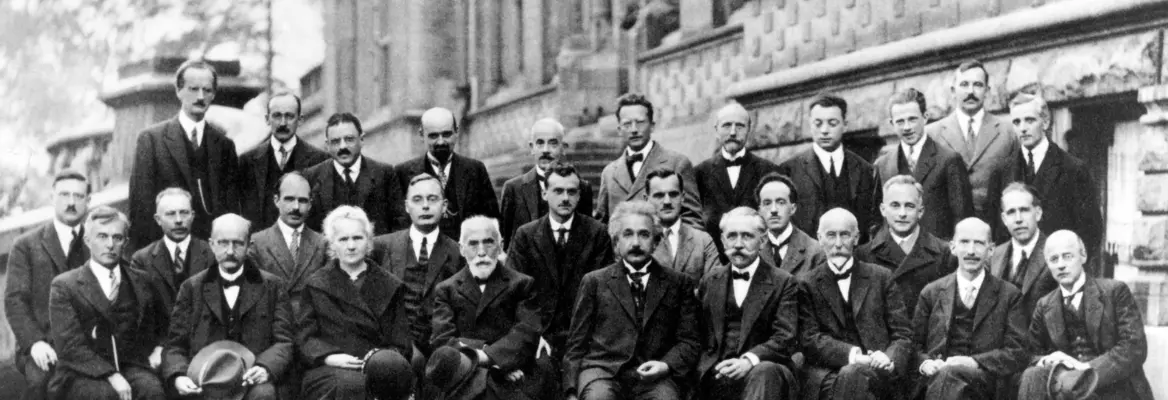

We place high epistemic value on expert opinion and when it reaches a consensus, we may view this as settled science. But, writes Miriam Solomon, we should not equate expert opinion with certainty. While expertise is a valuable guide to decision-making, experts can be prone to human error too. Laypeople can, and should, critically evaluate how expert consensus is reached.

We live in an immense, complex world, and frequently benefit from guidance from those with more information and experience—people we regard as experts—to make sense of it. Along these lines, we often use expert consensus as an indicator of what is known, and expert disagreement as an indicator of what is uncertain. So, for example, earth scientist and historian Naomi Oreskes appeals to the record of peer-reviewed scientific publications on climate change to argue that the public should listen to the expert consensus that there is anthropogenic climate change. Oreskes identified that those who publicly disagree with this consensus have not contributed to the peer-reviewed scientific literature on climate science, and in this way they are not experts with regard to the relevant subject matter, although they may have PhDs and even university positions in unrelated sciences.

___

Expert consensus should not be equated with certainty or truth. But experts are more likely to be correct than non-experts, and the agreement of experts with one another can provide additional evidence for the robustness of their conclusions.

___

Oreskes dissuades us from taking such non-expert disagreement seriously, especially since she also finds that it is politically motivated. The appeal to expertise encourages us to trust those who know more than we do about a particular matter and invites us to pay attention to reliable markers of expertise, such as publication in relevant peer-refereed journals. In traditional epistemological terms, it recommends deference to epistemic authority (or authorities). However, even experts are fallible. Expert consensus should not be equated with certainty or truth. But experts are more likely to be correct than non-experts, and the agreement of experts with one another can provide additional evidence for the robustness of their conclusions.

Oreskes’ approach implicitly relies on the trustability of the relevant experts, not only on their expertise. We need to know not only that experts are knowledgeable but that they are acting in the best interests of furthering knowledge. The integrity of science—its commitment to norms such as openness of inquiry, responsiveness to criticism, disinterestedness, etc. (see Merton (1942) and Longino (1990))—is vital for its trustability. Sometimes, this trust can be eroded. Philosopher of medicine Maya Goldenberg has explored what is needed for laypersons to build justified trust in vaccine research, mentioning concerns about Big Pharma producing biased research and concerns about the historical record of medical, scientific, and governmental communities’ willingness to use untested medical technologies on marginalized groups.

SUGGESTED READING

Experts and charlatans: The role of science in democracy

By Mauro Dorato

SUGGESTED READING

Experts and charlatans: The role of science in democracy

By Mauro Dorato

Join the conversation