We have known for decades that climate change makes them more likely, but extreme weather events are nothing new. Now, thanks to recent developments in climate modelling, meteorologists can quantify how much more likely increased greenhouse gases have made a particular extreme weather event. It remains a rapidly developing field. One of its pioneers, Peter Stott, outlines where the new science of extreme weather is today.

Earth’s climate is changing. As global temperatures rise, the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events around the world also rise. The science of event attribution is being developed to assess the extent to which recent extreme weather events are linked to human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases. Already this science has shown its potential by demonstrating that many events have been affected significantly by climate change. Further research will make it possible to pin down in more detail how a wider range of weather extremes have been affected by human actions.

Global temperatures are now over 1.1 degrees Celsius warmer than they were in pre-industrial times. This rise is mainly due to human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases. With rising temperatures have come more intense and frequent heatwaves, floods and droughts around the world. This year the Canadian temperature record was smashed: the 49.6C recorded in June was followed by devastating forest fires that destroyed the town of Lytton in British Columbia. Extremely heavy rain in central Europe in July led to flash floods that destroyed many thousands of homes in Belgium and Germany. A severe drought in Madagascar has left more than one million people short of enough to eat. There can be no doubt that extreme weather brings with it disastrous consequences.

Nevertheless it does not follow that all extreme weather events can be blamed on human-induced climate change. Climate has always varied naturally. In the past, long before the industrial era, weather was occasionally sufficiently unusual or extreme to cause substantial harm to large numbers of people. It follows therefore that some extreme weather events, even today, could be mainly associated with natural variations in climate. The natural El Nino phenomenon, for example, periodically brings warmer waters to the surface of the Eastern Pacific Ocean and this can lead to devastating flooding in Southern California and Northern Mexico.

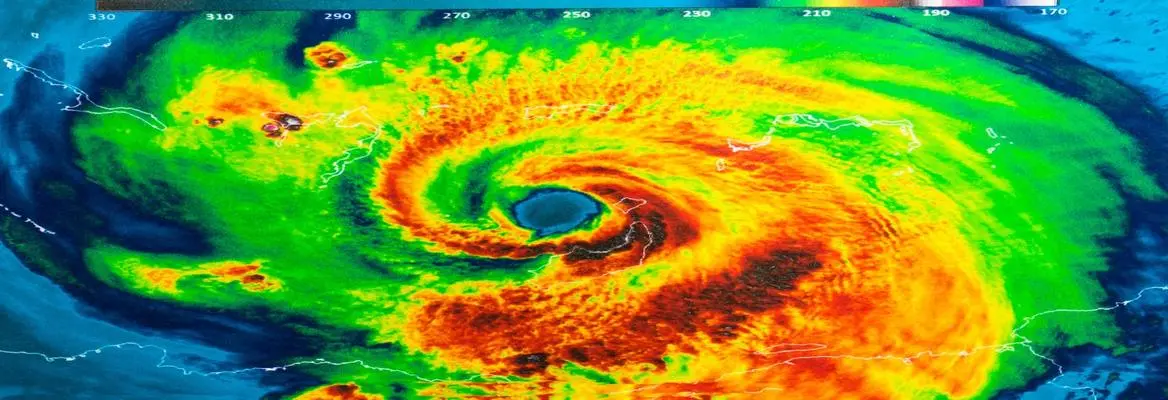

Despite these natural variations in climate, global average temperatures have now risen well outside the range of variations that can be explained by natural factors. This is increasing the risk of damaging weather around the world. As temperatures rise globally, the changes of record-breaking temperatures being observed locally increases. A warmer atmosphere can contain more moisture – about 7% for each degree Celsius of warming – which can lead to heavier rainfall in storms. With warmer ocean temperatures, storms are also potentially more energetic with stronger wind speeds. And as sea levels rise, due to expansion of warming sea water and melting of ice on land, there is an increasing risk of storm surges leading to over-topping of sea defences.

Increasingly, National Meteorological Services, like the Met Office in the UK, are being asked to provide updates on the meteorology of extreme weather as it occurs. In the face of increasing threats to their lives and livelihoods from climate change, people are no longer satisfied with knowing whether a recent extreme measurement was a record-breaker or particularly unusual. They want to know about the role of human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.

Join the conversation