Philosophers Thomas Hobbes and John Locke paint a picture of humankind living out short, brutish lives of self-interest, held together by a tenuous social contract of mutual benefit. But this liberal conception of the self is facing inevitable decline, argues Adrian Pabst, as we find ourselves thrown into a society characterised by community and cooperation.

In 1984, the American political philosopher Michael Sandel anticipated the effects of liberal individualism when he wrote that ‘in our public life we are more entangled but less attached than ever before’. Today the Covid-19 pandemic opens up the space for renewing a communitarian spirit of rediscovering the importance of attachment to people and place. Protective isolation has thrown us back onto family and neighbourhood, community and country. Yet at the same time, we find greater meaning in virtual connections worldwide, crossing liberal fault lines between the private and the public, the local and the global.

Binding together the tension between being embedded in places and being connected across the planet is our yearning for purpose – a natural desire for relations and institutions that provide meaning. If humans are meaning-seeking and story-telling animals, then the self only makes sense in something greater than itself. In our quest for a purposeful life, we discern at the heart of ourselves what the former chief rabbi Jonathan Sacks calls the greater human “We”, all the ties binding us together as humans who are social beings.

If humans are meaning-seeking and story-telling animals, then the self only makes sense in something greater than itself.

Beyond wealth and power, humans tend to seek mutual recognition – valuing everyone’s talents, vocations and contribution to society. Connected with this is our natural disposition for what George Orwell termed ‘common decency’ and honourable performance. We take pride in a job well done. The forging of a common life between separate selves that are also relational beings requires a politics based on a transcendent conversation, which can address deeper divisions around questions of shared belonging. Paradoxically, the search for the self leads us to discover the priority of the relational over the purely individual or collective.

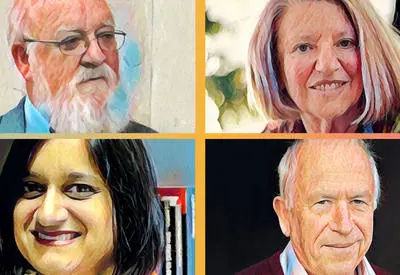

SUGGESTED READING

Leading philosophers at HowTheLightGetsIn Global

By

The pandemic has exposed just how vulnerable our lives are. From the “wet” markets of Wuhan and the cheap flights that carried this virus across the globe, to the locking down of countries and the crashing of economies, we have seen our fragile systems collapse. In one sense, the deadly disease threatened all of us, everywhere and simultaneously. Faced with our own frailty, we were being forced to confront existential questions about life and mortality.

SUGGESTED READING

Leading philosophers at HowTheLightGetsIn Global

By

The pandemic has exposed just how vulnerable our lives are. From the “wet” markets of Wuhan and the cheap flights that carried this virus across the globe, to the locking down of countries and the crashing of economies, we have seen our fragile systems collapse. In one sense, the deadly disease threatened all of us, everywhere and simultaneously. Faced with our own frailty, we were being forced to confront existential questions about life and mortality.

In another sense, the Covid-19 crisis was not the ‘great leveller’. It affected groups very differently, disproportionately hitting minority communities, those in precarious jobs and with underlying health conditions. Far from changing everything, the pandemic has accelerated and amplified disparities of power, wealth and social status that have developed for decades.

Those worst hit face greater economic interdependence but also greater social isolation than before. As the bonds of family, community, work, church and nation have declined, the scale of loneliness and seclusion is growing. Many of us are connected with one another online, but often we lack real relationships in the places we inhabit. The social theorist Sherry Turkle has given this paradoxical phenomenon the apposite appellation ‘alone together’.

Join the conversation