We should stop worrying about what’s right or wrong, or about reaching moral perfection. Instead, University of Colorado at Boulder philosopher, Alastair Norcross argues we should focus on how we can do better and avoid doing worse. Figures like Peter Singer make ethical demands of us that can be overwhelming. We must remember that every small step toward better counts.

A little over fifty years ago, the philosopher Peter Singer published an article that changed the way philosophers think and talk about the morality of helping others. In it, he appealed to a hypothetical example to motivate his claims. Here’s a version of it: On our way to give a lecture, we come across a small child, drowning in a shallow pond. No one else is in sight, and the child will be dead within minutes without our help.

We all agree that we should save the child. That’s easy. A bit of mud and water on our clothes, a bit of bother finding someone to give the child to, perhaps having to miss the lecture we were about to give, perhaps even having to forgo our lecture fee. But none of that could excuse our failure to save the child. Pretty much everyone agrees with this. Why? Because pretty much everyone cares about others, at least to some extent. That is, very few people are purely egotistical. Even if we are highly self-obsessed, and some of us certainly are, we also think that others matter too. We think it would be bad if that child were to drown in the pond. And if we could save the child, especially without a great deal of sacrifice on our own part, it would be bad not to. Not just bad, we might think, but wrong too. This much is fairly uncontroversial.

___

No matter how many we save, there are always more who need saving.

___

But then, of course, we notice that there are children drowning all over the world, most of them not literally drowning, but dying nonetheless, and death is death, whether from drowning, starvation, dehydration, or any number of other easily preventable but depressingly common causes. We may not be in close physical proximity to many of them, but we are in close causal proximity. With our credit cards and a few clicks on a website, or dialing a number on our phones, we can save a dying child, without getting wet or muddy or late for a lecture. It is easier to save those children, and, one may argue, the failure to do so is even more wrong. Singer’s version of right and wrong starts to feel like an overwhelming responsibility, and we need a different way to frame it.

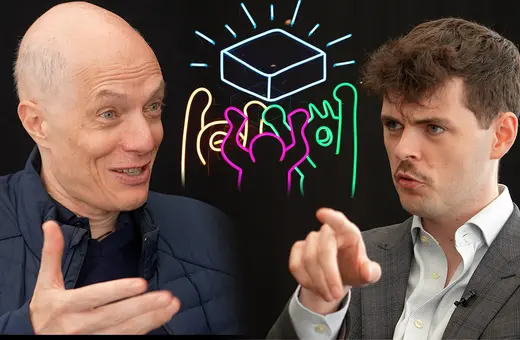

SUGGESTED VIEWING Challenging Peter Singer's ethics With Peter Singer

Perhaps we try to claim that these real children are different from the hypothetical drowning child in the pond. Relevantly different, that is. But how could that be? Most of them are thousands of miles away from us, but how could that make a moral difference? It couldn’t. Or perhaps we’ll try to claim that it’s not the physical distance, but the social distance that matters. The drowning child in the pond is a fellow citizen, or at least fellow resident, of the same country as us.

Join the conversation