We think we communicate and understand most deeply using language. But how can we say what words cannot express? Silence. Drawing on Wittgenstein and Heidegger, philosopher Steven Bindeman argues that language often keeps us separated from the world and is fundamentally incapable of describing it. Only silence can bridge the gap between the self and world.

This article is presented in association with Closer to Truth, an award-winning broadcast and digital media series that has run continuously since 2000. Closer to Truth's mission is to explore humanity's deepest questions with the world's leading thinkers and scientists.

If it is possible to mean more than we can say, then we will need to make use of silence. We can all recognize times when we were unable to articulate something important. Such moments place us in a situation of uncanniness, facing the disconnect between ourselves and the world around us. The common reaction to this disorienting experience is to fill it up with words, since it’s not the sort of thing we want to endure for long. When we bring silence to language, however, both the nature of language and the constructed world it encompasses undergo significant changes. As Kierkegaard once wrote, “Bring silence to people who listen and watch them take themselves to heart.”

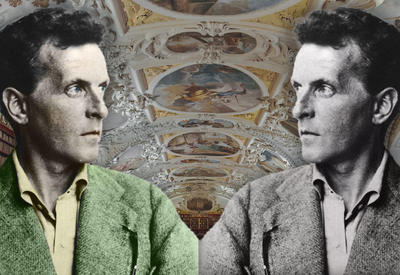

It’s no accident that the two most renowned philosophers of the 20th century, Heidegger and Wittgenstein, placed the phenomenon of silence at the center of their philosophies. When Heidegger designated nihilism as the inner logic of Western history, he was pointing to the disconnect between language and world; when Wittgenstein insisted at the end of his Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus that all discussions about ethics, values, and the meaning of life are meaningless because they have no clear referents outside language, he too was pointing to the same disconnect between word and thing.

___

As Kierkegaard once wrote, “Bring silence to people who listen and watch them take themselves to heart.”.

___

Like Heidegger, Wittgenstein thought deeply about the relationship between language and world, or words and things. Also like Heidegger, his ideas on this subject underwent drastic changes as he distanced himself from his original position. In his early work, the Tractatus, written in the trenches in the First World War, he sincerely believed that he had solved all of the significant problems that existed in the world of philosophy. In his preface to that work, he insisted that “the reason why these problems are posed is that the logic of our language is misunderstood.” He went on to say that “the whole sense of the work can be summed up in the following words: what can be said at all can be said clearly and what we cannot talk about we must pass over in silence.”

This did not mean that these issues were of no interest to him, however. It merely indicated that a different way of using language, perhaps under the ordinance of silence, must be invented. Most importantly, the essential dignity of “the unsayable” must be respected. Wittgenstein’s own thinking here can be extended by referring to what he wrote to his friend Paul Engelmann concerning a poem by the German poet Ludwig Uhland: “And this is how it is: if only you do not try to utter what is unutterable then nothing gets lost. But the unutterable will be—unutterably—contained in what has been uttered.”

SUGGESTED READING

Wittgenstein vs Wittgenstein

By Lee Braver

SUGGESTED READING

Wittgenstein vs Wittgenstein

By Lee Braver

Join the conversation