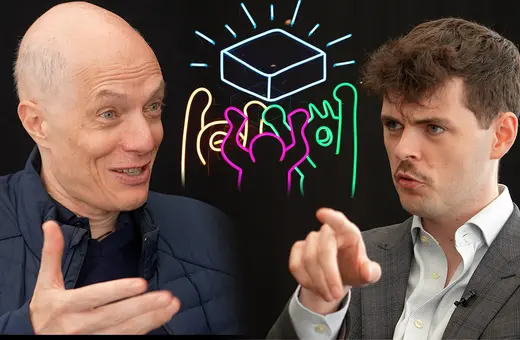

A core value of Western liberal democracy is freedom, and we tend to assume that the more choice we have, the freer we are. But that’s a dangerous illusion, argues psychologist Barry Schwartz. There quickly comes a point when too much choice—over what we eat, what jobs we do, who we date—leads to paralysis, anxiety and misery. Yet we measure economic progress by how many new choices the market churns out. The million-dollar question, Schwartz urges, is whether we can we reintroduce healthy limits into our lives without undermining liberal-democratic ideology itself.

Alasdair Craig: Should we strive for the best in life, or is doing so making us miserable?

Barry Schwartz: Well, it seems sensible that we should try for the best in life. But as an empirical matter, when we try for the best in life our standards for what counts as best keep going up, and even though we do better on Tuesday than we did on Monday, we don’t do as well as we expected to do. So we end up feeling disappointed.

So the question is whether your focus should be on how well you’re doing objectively (how big is your bank account?) or how well you’re doing subjectively (how good you feel about how big your bank account is?). And there’s a trade-off, because often the better you do objectively, the worse you feel subjectively—at least in a world where there are so many options that you convince yourself that something other than what you chose would have worked out better.

So, you know, I'm a striver. I try to get excellent things and do excellent things, but I also know that if I had very high standards, I would never have published a word, let alone a book, because I know what's wrong with everything I write as I write it.

AC: We tend to think that a good society is one which maximizes the amount of choice that we have. But you think that having too many choices makes us unhappy. Why?

BS: Western democratic societies deeply value freedom, and you don’t have freedom unless you have choice. And it seems that the more choice you have, the more freedom you have. You can always ignore options if you don’t need them, so surely adding options will make you better off. So, every new thing you add improves somebody’s life, and makes nobody’s life worse off. What could be better than that?

___

The better you do objectively, the worse you feel subjectively

___

That is logically compelling. But psychologically, what happens when there are lots of options is that people feel that they ought to get the best one out there. And you know, that’s feasible, maybe when there are half a dozen choices out there, but when there are 100 out there, it’s not feasible. And in the digital age, when there are thousands out there, it is certainly not feasible.

And this produces two major problems. First, people end up not being liberated by all the options, but rather paralyzed—they can’t pull the trigger. If they just spend another two minutes looking, they’ll find something better. And second, when they do choose, and they choose well, they are still disappointed with the result, because somewhere out there was an option that would have suited them even better. So again, you end up doing better objectively with all these options but feeling worse about how you’ve done.

Join the conversation