We tend to view the particular financial norms of our time fatalistically, as an inevitable reality of our circumstances. But the ways in which economic activity creates wealth change over time – economist and sustainable finance specialist Thomas Lagoarde-Ségot argues that the concept of the accumulation regime teaches us that the debt-loaded, extractive system that currently shapes our lives won’t last forever, and other options are available.

Financial markets and banking institutions have become the command center of the global economy. The decisions of governments, companies and individuals are guided by a gigantic network of interconnected financial balance sheets on millions of computers, in which money acts as a universal language. For many policymakers, as well as ordinary citizens, there is nothing more to economic reality than the information provided by this network, which seems, at first glance, capable of revealing the real and only truth about the economy. This truth, in turn, shapes our destiny.

While it would be very difficult to envisage running an economy without a financial system, the current structure of finance and the economy is, however, idiosyncratic. Financial interests, institutions and narratives change over time. Understanding this is vitally important for understanding the global economy. When it comes to finance, not every Euro is created equal, and recognising that our current system is but one setup of infinite possibilities opens the door to change.

Since the 1970s, a group of economists known as the Regulation School have looked at how institutional arrangements connect financial systems and the rest of the economy. This resulted in Robert Boyer’s concept of an accumulation regime. An accumulation regime is defined by Boyer as ‘a set of regularities ensuring a general and relatively coherent progression of capital accumulation’ – or the conditions that ensure that capital can accumulate, creating profit.

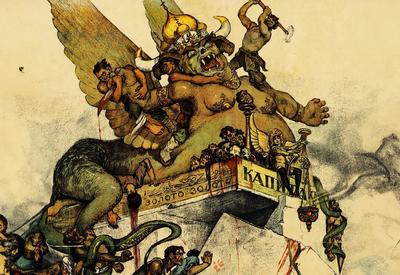

Regulation school economists have pointed out that the Fordist accumulation regime (where capital accumulation was accrued primarily through commodity trade) stands in sharp contrast with the finance-led accumulation regime (where profits accrue increasingly through financial channels) which has been dominant in most advanced economies since the 1980s and which most of us have come to consider a natural.

___

As a social compromise between labour and capital resulted in the distribution of increasing productivity gains between workers and the owners of assets, or rentiers.

___

One key lesson is that the institutional arrangements governing the relations between the financial system and the economy are temporary, and yet they have profound implications for both social and economic welfare. They can determine our wealth and quality of life – as such, we need to understand their impact.

Consider what happened at the Mount Washington Hotel, during the June 1944 Bretton Woods conference. The 700 global delegates, led by Harry Dexter White and John Maynard Keynes, agreed that some unseen international monetary and trade system had to be devised that would reverse the world’s fall into poverty and conflict. They envisioned a global financial architecture which, although not perfect, could arguably be considered as one of the most enlightened events of human history, as it sought to deliver prosperity for all countries.

SUGGESTED READING

How the free market is failing

By José Miguel Ahumada

SUGGESTED READING

How the free market is failing

By José Miguel Ahumada

One important feature of the Bretton Woods system is that it ‘euthanized rentiers’, radically limiting their power by restricting international financial flows and speculation, while giving democratically elected governments ample policy space to pursue domestic objectives, such as full employment and price stability.

Join the conversation