In a world of vast inequality, morality demands more than good intentions. Is giving just 1% of your income to effective charities the minimum for being a decent person?

Most of us like to see ourselves as good, morally decent individuals. What’s more, we largely agree on what it means to be a decent person. You don’t just have to pay your taxes and not harm others. You have to go beyond that by, for instance, being kind, treating others with respect, and supporting your friends, family and neighbours.

What our modern secular society lacks, however, is a clear idea of how a decent person should give to charity. We live in a world of staggering inequality and extreme need. There will always be more we could do. When have we given enough - not to be a saint, but to clear the bar of decency?

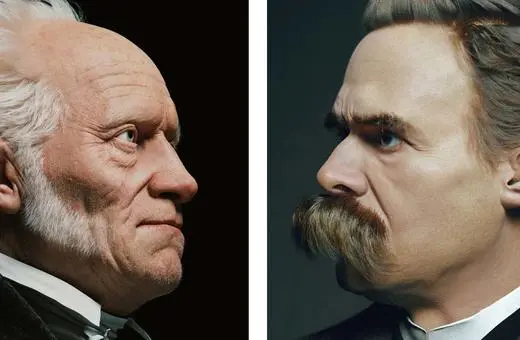

One extreme view comes from the philosopher Peter Singer. In his famous thought experiment, you’re walking past a shallow pond and see a child drowning. You could save the child—but it would ruin your expensive new shoes. Most people agree that it would be wrong not to wade in. Singer proposes the principle that if we can prevent something bad from happening, without sacrificing anything of comparable moral importance, we ought to do so.

Singer extends this principle to charity. He points out that, everyday, we’re like the person on the side of the pond. We could sacrifice some of our material wealth by giving to charities and this would be a great benefit to others at a small cost to us. If we’re required to sacrifice our shoes, why aren’t we also required to give?

Yet, if other people matter morally as much as we do ourselves, the terrifying implication is that we should keep giving until we’re left with nothing - besides that which we need to survive.

That is a crushing standard. Even Singer admits he doesn’t meet it. And, crucially for our purposes, giving away all your spare income is far more than just decent: it’s saintly. Clearly, you can be a morally decent person without being a saint. We are asking what a decent person should do, not what a saint would do.

At the other extreme is the idea that we don’t need to give anything at all. That’s too lenient. Moral decency may not require everything, but it definitely requires something.

SUGGESTED VIEWING Challenging Peter Singer's ethics With Peter Singer

So, where’s the line?

Many people think giving should fall to “the rich.” But the rich include more people than you might think. If you earn the median UK income—around £37,000—you’re in the top 2% of the global income distribution. Those of us in this bracket often don’t feel rich because we live in wealthy societies and we engage in upwards comparisons, paying more attention to those better off than us that those worse off. Resultantly, we can suffer from a sort of ‘money dysmorphia’ - an analogue of body dysmorphia - where we see ourselves as poorer than we are.

But most readers of this article are exceptionally fortunate. It’s been estimated that 117 billion members of our species have ever lived. That means that if you’re in the 2% richest today, you’re likely in the 0.1% richest people in history. Surely the richest 0.1% can afford to give a bit - even if they already help strangers in other ways.

Join the conversation