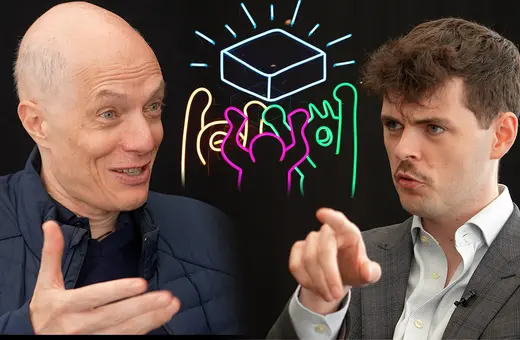

In this interview, I sit down with Simon Critchley, Hans Jonas Professor of Philosophy at The New School for Social Research in New York, to explore his provocative new book, On Mysticism. Drawing on medieval Christian figures like Julian of Norwich and Marguerite Porete, Critchley argues that ecstatic experience, intense love, and a willingness to be “outside oneself” can offer a counterbalance to the narrowly rational outlook dominant in modern philosophy. Throughout our conversation, he probes the boundaries of faith and reason, discuss the possibility of maintaining mysticism alongside science, and question the role of philosophy itself in shaping our cultural consciousness. What follows is only a short, edited extract from Critchley’s call for more openness, both in our thinking and our collective search for meaning. Link to the full interview.

Omari Edwards: You begin your book by contrasting Hamlet’s melancholic skepticism with the promise of mysticism. How would you define mysticism, and why did you choose Hamlet as the starting point for exploring it?

___

I see Hamlet as the quintessential philosopher, melancholic, who is the cleverest person we could imagine. And he's sad, he's depressed.

___

Simon Critchley: Mysticism is experience in its most intense form, experience in its most intense form. So what mysticism is about, who these mystics were, were people that were able to experience an intensity of aliveness and and love and a sense of being outside themselves, ecstasy. So, the subtitle of the book in in the UK is the experience of ecstasy. That sense of being outside oneself is really what I'm trying to say. That's the core of mystical experience. And we can, we can get there by pushing ourselves out of the way as much as possible.

I see Hamlet as the quintessential philosopher, melancholic, who is the cleverest person we could imagine. And he's sad, he's depressed, and his extraordinary intelligence leads to a melancholy. It leads, in his case, to the extinction of the capacity to love. I see that melancholy, rational, skeptical disposition all over the place in philosophy. And so mysticism poses a significant challenge to that and a different way of opening things up.

Analytic philosophy is often seen as radically opposed to mysticism and even its opposite. Do you think analytic philosophy is fundamentally flawed?

The modern idea of philosophy as a critical, rational and naturalistic practice... focus[es] very much on questions of its relationship to science, a kind of under laborer to science, as John Locke described it.

___

Philosophers are quite awful people most of the time.

___

Philosophy is now just a critical enterprise which I think at the edges flaps into a cynicism. It’s usually impossible to persuade philosophers of anything, in my experience and I’ve been doing this for 35 years, teaching—philosophers are quite awful people most of the time...

The promise of philosophy was not just analytical rigor. It was a kind of manic, divine love. That’s what you find in you know, in Plato’s Phaedrus, in the Symposium, and even in boring old Aristotle... a contemplative life would be the life of the gods.

What do you mean by saying that philosophers should cultivate openness?

I find that the modern idea of philosophy leads to an incredibly narrow understanding of philosophy. We end up misrecognizing the history of philosophy and imposing our current mode onto the historical accounts. So, the least we can do is trying to open our minds a little bit.

___

Philosophy has to be part of culture. Philosophy isn’t something that takes place in a handful of academic departments.

___

Join the conversation