The relationship between morality and emotion has divided thinkers for centuries. Most contemporary ethical systems demand impartiality; that we should not allow emotion, particularly empathy, to distract us from doing what is morally right. In this article, Heidi L. Maibom rejects this position. Here, she argues that empathy is both an essential and necessary tool to understanding human nature, and provides a blueprint for how we should devise our moral systems.

To most people, it seems obvious that empathy has something important to do with morality. After all, when we feel with someone who suffers, we often think it is wrong that the person suffers, and if someone has caused their suffering, we tend to think they were wrong to do so. Saints, like Saint Francis or Mother Theresa, are typically moved by their concern for the suffering of others. And I, at least, use my empathy as a moral guide. If I empathize with the suffering of caged animals, say, I begin to think that caging animals is wrong. Morally wrong.

It might therefore come as a surprise to realize that a handful of philosophers and psychologists have concluded that since we sometimes don’t feel empathy when we judge something to be wrong or act morally, and since we can empathize without judging a wrong to have been committed or, indeed, without being motivated to act morally towards someone, empathy has no role in morality. And not just that, Jesse Prinz and Paul Bloom claim empathy actually is bad. Why? Because empathy focuses our attention on just a handful of people whereas morality require us to care equally for all, itmakes us make worse choices.

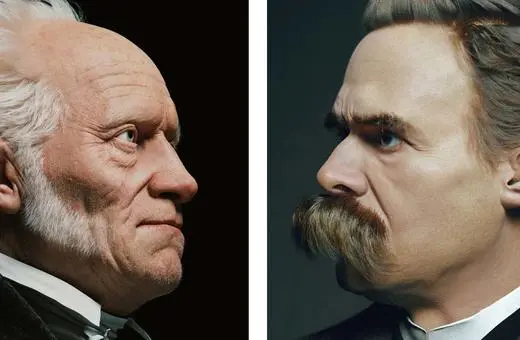

___

The key disagreement about the role of empathy in morality boils down to this question. Can we truly understand what matters to other people, what moves them, what damages their wellbeing, and so on without empathizing with them?

___

Considering these powerful criticisms, it seems surprising that philosophical heavyweights, such as David Hume and Adam Smith, could have thought empathy was foundational to morality. It is, Smith argued, because others’ suffering makes us suffer that we come grasp their suffering as suffering, and through our own suffering come to care about it and regard it as a prima facie case of something wrong. Smith also thought that the way we avoid bias and partiality is by taking the perspective of a so-called Impartial Spectator. Such a spectator is not emotionally involved in what is happening, knows all the relevant facts about it, and is indifferent to the goals and interest of the people involved. This, Smith claims, allows us to make true moral judgments and it would avoid the charge of bias, since she cares no more for one person than any other.

Join the conversation