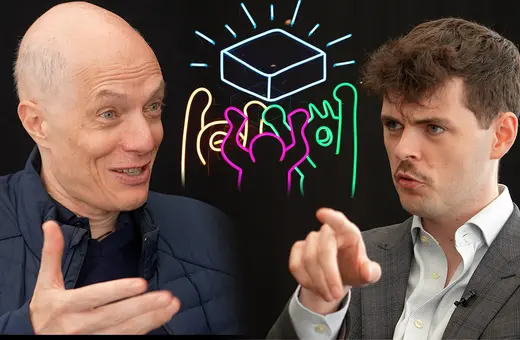

Nolen Gertz is Assistant Professor of Applied Philosophy at the University of Twente, Netherlands, Senior Researcher at the 4TU.Centre for Ethics of Technology, and the author of The Philosophy of War and Exile: From the Humanity of War to the Inhumanity of Peace (Palgrave 2014).

Describing himself as a “continental philosopher trying to live in an analytic philosophy world”, Gertz’s career as a philosopher began at The George Washington University before he went on to complete his PhD at The New School for Social Research, His philosophical interests include applied ethics, social and political philosophy, phenomenology, existentialism, and aesthetics. Amid his engagements as an ‘ethicist for hire’, he is currently focused on investigating the relationship between nihilism and technology.

—David Maclean

DM: Why do baby names, particularly unusual ones, provoke such a strong reaction?

NG: I think it’s certainly something that stressed me out, both as a parent and as someone who has a somewhat unusual name. I’ve had the experience of people actually telling me that my name is spelt wrong. One of the first things people ask is what your name is, or thinking about those “Hello my name is…” stickers – we put a lot of stock in that information and we overdetermine that the name is somehow representative of the person’s character, lineage, future, etc. And thus you also get a sense of what the parents envisioned for the child, so this also reflects the parents’ character. I think that this idea that the name means something is very important for us. So I think that also part of it, from an existential perspective, is how important it is that we reduce things to their names, whether humans or objects.

DM: The existentialists would of course argue that while none of us choose to be born, none of have a say in what we’re called either. Do you think that when we name babies we are putting essence before existence?

NG: Well Søren Kierkegaard, for example, espoused the idea that to label me is to negate me. And this is especially true for someone like Kierkegaard who gave himself so many names. It was very important, this idea that you could, in a sense, recreate yourself by recreating your name – and yet because of socioeconomic and legal institutions you’re still tied to your name, you can’t escape it fully. Even if you legally change it, there’s still a record of it, and then, of course, the fact that you changed the name becomes more information that people compile about you. So I think that there’s this idea, like you said, that once I give you a name, you’re sort of locked into a certain path. There’s a great Seinfeld joke that illustrates this about the incomprehensibility of a hitman named Jeeves.

On the point about mapping out the future, if I named my child something obviously very unusual, this would raise a few eyebrows among people who would believe that I’m being very unethical in setting the child up for ridicule. However, the name I’ve chosen reflects the identity that I envision for my child.

___

"When people ask you who you are, why do you give your name – as though that means something?

___

DM: How would an ethicist respond to this conflict of interests?

Join the conversation