On the second day of HowTheLightGetsIn festival at Hay, one of the panel debates turned to the question of whether lying is necessary, and even justified, for the smooth running of society. Psychologist Simon Baron-Cohen, philosopher of swearing Rebecca Roache, and post-realist philosopher Hilary Lawson, argued over whether lying has anything to do with the truth and whether honesty is a crucial virtue, only to be violated in extreme circumstances, or whether honesty is in fact inappropriate more often than we think.

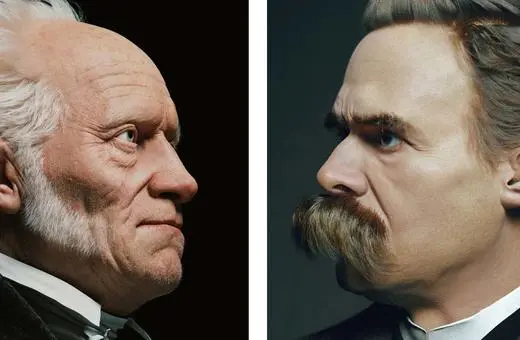

Hilary Lawson, Simon Baron-Cohen, and Rebecca Roache debate the virtue of honesty. Samira Shackle hosts.

Nobody likes people lying to them. But don’t we all think it’s sometimes acceptable to do so? Even the morally right thing to do? Should we really all be as pedantic as Kant would like us to be and never lie, no matter what? Would society even function if everyone was 100% honest all the time? It’s hard to imagine. Yet, where do we draw the line? Are politicians allowed to lie a bit, just like the rest of us? And how can we tell whether someone is lying or not in an age that many have come to accept that an absolute, universal truth might be a fiction. These were some of the questions that the Simon Baron-Cohen, Rebecca Roach and Hilary Lawson grappled with on a panel during the second day of HowTheLightGetsIn.

Rebecca Roache, a philosopher of language and swearing, reminded us of Aristotle’s view that there is no one single virtue, and we need to exercise them all in moderation in order to lead a good and fruitful life. So even though honesty is indeed a virtue, it can sometimes clash with other equally important ones, like kindness. In those cases, the right thing to do, morally speaking, might be to be dishonest. It’s all a balancing act.

The psychologist and neuroscientist, Simon Baron-Cohen, most famous for his work on autism, agreed. What’s more, there seems to be some neuroscientific evidence that lying can be guided by a concern for the other person. As it happens, our ability to deceive successfully and flexibly, in many different contexts, unlike other animals who can only do so for one specific purpose (think of the insect pretending to be a stick, or the fish pretending to a rock) is because of our empathy circuit: our ability to think of other people’s thoughts and feelings. And since lying is, according to Cohen, our ability to make people believe something is true when in fact it’s false, having the skill to imagine what other people are thinking is necessary.

Join the conversation