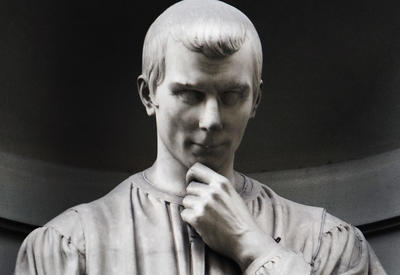

Our current moment is defined by an obsession with the new, a new for new's sake that no longer exists on a timeline, but has rather become epistemologically, spiritually, necessary. This obsession was born with modernity, the Renaissance, the 'discovery' of the New World and the desire to have a blank slate, a new society without ties to the past. As we know, that never existed. Professor Francesco Erspamer contrasts this with political philosopher Machiavelli's different modernity: one that privileges, above all, duration in time. He defends a reformulation of the present moment that would better allow us to survive current crises.

The basis of this short article, and in general of my studies in recent years, is the conviction that modernity, as it affirmed and represented itself, was based on a single concept: the new. Which at the dawn of the 16th century began to be understood no longer in a temporal sense, to indicate a recent thing or event, but in an epistemological sense, to qualify anything that could guarantee superior knowledge without requiring the validation of pre-existing paradigms and authorities. Indeed, scientific revolutions, Thomas Kuhn explained, occur and multiply when ignoring and forgetting previous conceptions proves easier than revising them or integrating subsequent discoveries with them. Modernity as we know it, and to which we belong, is conditioned by this utilitarian paradigm of change: progress, development, growth, fashion, avant-garde, innovation, are just some of the many terms that confirm the hegemony of the new. But the degradation of the environment, rampant individualism, technocratic nihilism, compulsive consumerism, show that one does not live by novelty alone. Perhaps we need a different modernity, perhaps a different modernity is possible. To begin to imagine it, I suggest we go back to one of the witnesses and protagonists of the birth of modernity: Niccolò Machiavelli.

SUGGESTED READING

Liberalism's fatal flaw

By Stuart Gray

SUGGESTED READING

Liberalism's fatal flaw

By Stuart Gray

Some consider the Renaissance the dawn of modernity and Machiavelli the inventor of modern politics. I agree, but with the caveat that his was not our modernity—the line that leads from Galileo to Elon Musk—, which could be called successful modernity precisely in the sense that what qualifies achievements is their success, a past participle (of the Latin verb succedere “to come after”), thus founded on a utilitarian and non-teleological conception of the world and society (and, of course, of economics), privileging results rather than goals. Fully modern was Machiavelli, indeed, but of another modernity, which it might be vital to recover in order to save an all too successful modernity from itself.

___

One need only note the obsession, certainly in my university, with a device such as the ‘start-up’, that is to say, with a project that deliberately emphasizes only the moment of beginning, and not a past beginning which has become origin, but rather a future beginning, the assumption of a beginning.

___

These are reflections prompted by the current crisis in the humanities. Despite its complexity, I tend to trace it back to a single cause, highlighted in the title of this article: the renunciation of duration, even the intent to last, as if it were a problem or a fault.

Join the conversation